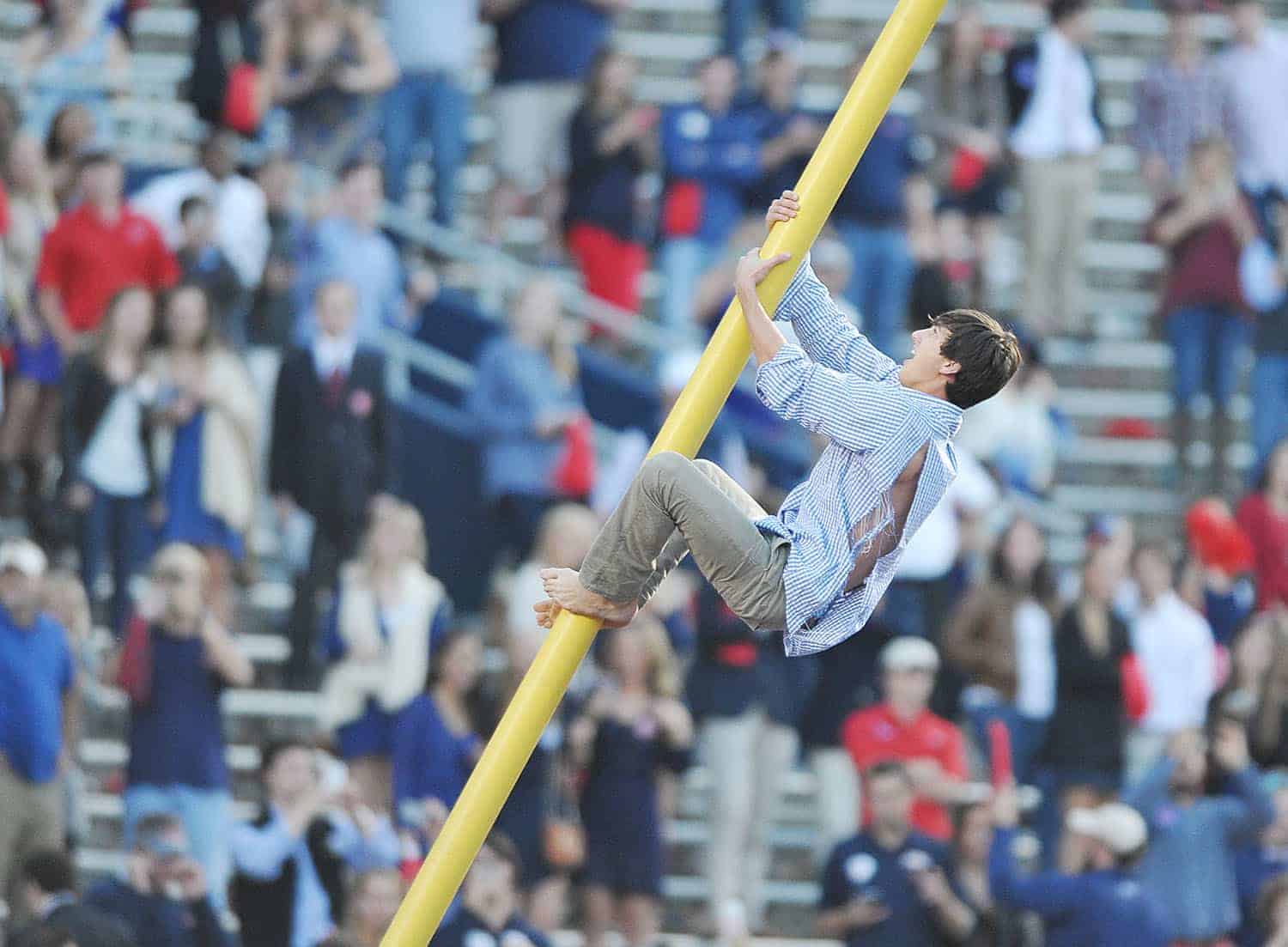

The moment the first goalpost buckled beneath the weight of students determined to uproot it, the history of Vaught-Hemingway Stadium suddenly recategorized into everything that happened before the Ole Miss Rebels’ historic 2014 upset against Alabama and everything that would happen after.

It was unquestionably the most stunning win in the modern era of Ole Miss football with a team expected to do pretty well that season—just not beat-the-No.-1-team-in-the-country well. Fans flooded the field. Quarterback Bo Wallace rose above the crowd atop the shoulders of a group of worshipful students. Police escorts rushed Alabama coach Nick Saban to the locker room to escape the pandemonium, protectively clotheslining an overeager fan along the way.

Fans who opted to stay in the stands stood in shock, absorbing the improbable scene and the realization that the win wasn’t just relevant to Mississippi, but the entirety of college sports. A win with enough head-shaking disbelief behind it to be an integral part of the team’s story for years to come, not unlike the annual replay of Billy Cannon’s punt return in the Rebels’ infamous 1959 Halloween heartbreaker against LSU.

Even more improbable was the following season when Ole Miss gave Alabama its only season loss for the second-straight year, this time at one of the most intimidating stadiums in the SEC—Bryant-Denny. The win was just as remarkable, considered by many to be even more significant considering the Rebels had beaten the Tide in Tuscaloosa only once before. But the wild scene in the Vaught the previous season will likely always speak louder for the fans who lived it. It’s one thing to beat someone in their house. It’s another to do it on your own turf when the world—and even you—expected the opposite to happen.

Storied stadiums abound in college football—from LSU’s Death Valley to USC’s Coliseum to the Horseshoe at Ohio State. But Ole Miss’ football culture has long been dominated by the appeal of the Grove and the school’s over-the-top tailgating tradition, leaving Vaught-Hemingway to play second fiddle on game day. It’s become the norm for hundreds of fans to bypass ticket prices and the 5-minute walk to the stadium in favor of watching the game on TV in the Grove. And if all hope for a win dies before halftime, those inside the stadium can retreat to their oak-shaded hamlet to drown their sorrows, Solo cup in hand.

Most Ole Miss football traditions are relatively new for a university known for ongoing battles over historical and cultural preservation. Before Rebels became the school’s nickname in the late 1930s, the school’s athletic teams were known as the Red and Blue and later the Mississippi Flood. Before fans protested the gradual phasing out of “Dixie,” once considered the school’s unofficial fight song, there was once widespread nostalgic longing for a game-day tune known as “Give ‘Em Hell, Mississippi.” The first renditions of Colonel Rebel, the controversial former mascot, emerged on the scene in 1937, nearly 90 years after the university was founded. Even “Hotty Toddy,” the school’s seemingly innocuous chant, has evolved from being a phrase once shunned by school officials to prevailing as the university’s signature rallying cry.

The same goes for the university’s renowned tailgating scene which is the school’s main claim to fame when it comes to the bigger, better, it-just-means-more SEC. Though the Grove’s role as the central pregame gathering spot is a longstanding practice, its reputation for upscale tented tailgating wasn’t born until the 1980s as the product of dismay over fans parking on the grass and damaging the trees.

For a sport so culturally rooted in the idea of tradition, few things about college football are constant. Coaches are hired and fired. Players come and go. And while college stadiums are often renovated to accommodate demand and deluxe fan experiences, rarely can they be completely demolished or abandoned to build something on a different site. It is for this reason that these stadiums serve as modern-day monuments to college football, its significance crafted from steel and concrete.

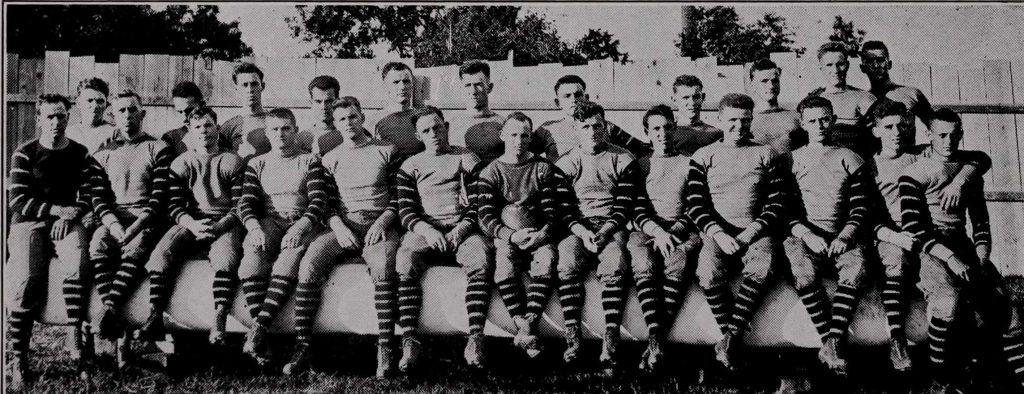

The 1914 Ole Miss football team (above) was the first squad to play on the site where Vaught-Hemingway sits today.

Jackson Daily News, October 1914

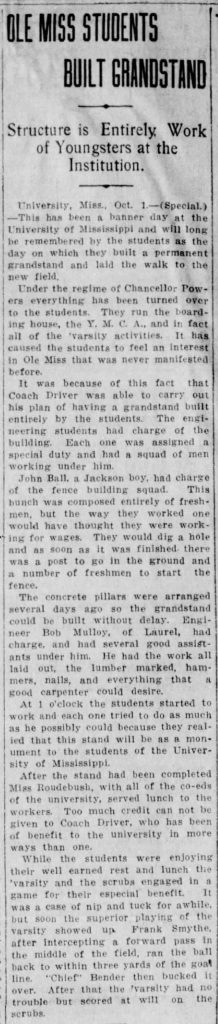

When a group of Ole Miss engineering students was tasked with building the first football grandstand on the site of the present-day stadium in 1914—not 1915 as it’s often cited—they did so with full understanding of what their efforts represented. In Joseph Powers’ first year as chancellor, he called on students to take charge of managing several things on campus, including varsity sports, giving the student body “an interest in Ole Miss that was never manifested before,” according to a report in the Jackson Daily News.

It came as no surprise when Powers approved football coach William “Billy” Driver’s idea for a grandstand constructed entirely by university students. On October 1, 1914, nearly 100 years to the day before the Alabama upset heard ‘round the world, students spent the day constructing the university’s first football venue at the same site where Vaught-Hemingway sits, celebrating their efforts with a friendly varsity vs. scrubs scrimmage after the work was complete. That same week, Mississippi State, then Mississippi A&M, constructed its first field structure on the site of what is now Davis-Wade Stadium.

During the first half of the century, as football firmly cemented itself in the South as the end-all-be-all of sports, it was commonly front-page news across Mississippi whenever changes were made to either site.

In October 1922, the university announced plans for a concrete stadium to be drawn up by engineering students and erected by alumni. Three years later in 1925, both Ole Miss and Mississippi State launched identical campaigns to raise money for new stadiums by selling insurance policies to students and alumni—even having a contest to see which school would raise the money first.

Sports journalists often referred to the stadium as “Ole Miss stadium” or other generic names, but in 1939 the alumni association voted to name it after Judge William Hemingway, the longtime chairman of the university’s athletics committee credited with restoring the school to a “place in the football sun.” In Oxford a month later, in front of what was then the largest crowd in state history to watch a football game, underdog Mississippi State defeated Ole Miss 18-6. Over the next several years, Hemingway Stadium remained in desperate need of expansion, often hosting capacity crowds and sometimes having to cram extra seats in the 26,000-seat stadium just to accommodate the popularity of the sport and the growing annual rivalry between the Rebels and MSU. By the end of the 1940s, plans set forth by then-athletic director C.M. “Tad” Smith would grow Hemingway Stadium into a 34,500-seat capacity venue.

The Clarion-Ledger, December 2, 1956

Despite the improvements, which were designed to attract higher attendance and offer further incentive for conference foes to play Ole Miss home games in Oxford rather than Memphis or Jackson, Smith battled an image problem in the 1950s when several SEC schools, Alabama, LSU and Tennessee among them, sought to negotiate the home site to larger cities rather than making the trip to remote Lafayette County.

Legendary Alabama coach Bear Bryant (left) and Johnny Vaught leave the field at Mississippi Memorial Stadium in Jackson, where the Crimson Tide typically played away games against Ole Miss until 1993 when it was moved to Oxford.

Schools reluctant to sign home-and-home series with the Rebels often cited the lack of satisfactory crowds due to Oxford being off the beaten path. At a SEC athletic directors meeting in Birmingham in 1954, Smith shared his apparent frustration with the issue, refuting the claims of weak attendance that had acted as a pass for SEC foes to avoid playing in Oxford. “We’re just a small school, but our teams have had no trouble drawing the crowds,” Smith said. “Good squads will draw crowds anywhere.”

After LSU played in Oxford in 1960, Ole Miss agreed to concede the next home game location to the Tigers, making for three consecutive match-ups in Baton Rouge. That season, Johnny Vaught’s losing record in Hemingway was strikingly low—largely because by that time he had coached only 33 of 130 total games in Oxford. In 1963, Alabama and Florida inked a future series deal with Ole Miss under the condition of playing in Jackson. Smith’s efforts to make Oxford the premier game-day experience for Ole Miss football only became more difficult and the situation was no different down in Starkville.

That same year, much was said about the University of Tennessee’s demands to play Ole Miss and Mississippi State in Memphis rather than on their respective campuses, despite the fact both schools’ stadiums could seat 5,000 more than Memphis’ Crump Stadium—not to mention the fact there was little home-field advantage for either Mississippi team when playing in Tennessee. This reluctance hit Ole Miss harder than its in-state rival as the Rebels, one of the winningest teams in the nation during its Vaught-led glory days, faced increased scrutiny that their past successes were only due to weak scheduling. After all, some games had to be played in Hemingway each year out of fairness to students enrolled at the university, but with top opponents unwilling to make the trip, Ole Miss often had to book non-conference games to fill those slots.

The 1970s and ‘80s weren’t always kind to Ole Miss regarding wins and losses, but it was a time of tremendous improvement to stadium amenities and the on-campus game-day experience. Though the Egg Bowl and most big SEC games were still played in Jackson during this time, Hemingway Stadium—officially named Vaught-Hemingway in 1982—came into its own in the late 1980s with a new press box, aluminum sideline seating and a club section. Lights were finally added to the stadium in 1990, and by 1998, a Jumbotron and Rebel Club seating had elevated the stadium’s status despite still being one of the smallest-capacity venues in the SEC. With Eli Manning’s era ushering Ole Miss football into the early 2000s with a renewed sense of being a contending team throughout the SEC and the nation, the 21st century brought about steady expansion, high-profile matchups and an uptick in national coverage due to the university’s increasingly popular tailgating tradition that branded the school as a place incapable of losing parties no matter how many times they lose a game.

Change to the Vaught during this time wasn’t merely cosmetic. The university underwent tremendous and often contentious social transformation starting in the early 1980s with Vaught-Hemingway often being ground zero for how the school chose to grapple with race-related issues and its branded ties to Confederate culture in almost every aspect of the game-day experience. When John Hawkins became Ole Miss’ first black cheerleader in 1982, his refusal to fly the Confederate flag—which had been a constant game-day accessory for decades—was met with national attention. The flag, which had reemerged symbolically across the South during the civil rights movement as means of protesting integration, was being seriously addressed in its various iterations for the first time in public schools and government buildings around the country. Ole Miss, which not only clung to the flag but also its Confederate mascot, Colonel Rebel, and several variations of Dixie played on game-day by the Ole Miss Band, was a natural target for criticism and questioning, particularly as its African-American enrollment hit a major slump in the 1980s.

Change to the Vaught during this time wasn’t merely cosmetic. The university underwent tremendous and often contentious social transformation starting in the early 1980s with Vaught-Hemingway often being ground zero for how the school chose to grapple with race-related issues and its branded ties to Confederate culture in almost every aspect of the game-day experience. When John Hawkins became Ole Miss’ first black cheerleader in 1982, his refusal to fly the Confederate flag—which had been a constant game-day accessory for decades—was met with national attention. The flag, which had reemerged symbolically across the South during the civil rights movement as means of protesting integration, was being seriously addressed in its various iterations for the first time in public schools and government buildings around the country. Ole Miss, which not only clung to the flag but also its Confederate mascot, Colonel Rebel, and several variations of Dixie played on game-day by the Ole Miss Band, was a natural target for criticism and questioning, particularly as its African-American enrollment hit a major slump in the 1980s.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the university phased out many of these symbols, starting by banning sticks and large banners from the stadium to prevent fans from waving Confederate flags. Right before Eli Manning’s senior season kicked off in 2003, university leadership with former Chancellor Robert Khayat at the helm, dealt the most controversial blow to the school’s racially divisive symbolism by removing Colonel Reb from the sidelines, leaving the university without an on-field mascot for the next seven years.

During former Chancellor Dan Jones’ first year in 2009, he helped students lead efforts to end the playing of “From Dixie with Love” on game day due to students screaming “the South will rise again” during the tune’s climax. The following semester, a student referendum asked the student body to vote on whether they wanted to lead efforts to develop a new mascot. The vote was yes, and a year and a half later, Rebel Black Bear appeared on the sidelines for the first time.

Despite the expected polarization among fans and alumni over longtime symbols being removed and replaced, it was undeniable that reshaping the university’s image, particularly on game day when there’s often a national crowd looking in on the South, ushered in a new era for the university across the board, including athletics.

Mississippi Rebels’ quarterback Bo Wallace (14) is carried off the field by fans following his team’s win over Alabama at Vaught-Hemingway Stadium in Oxford, Miss. on Saturday, October 4, 2014. Mississippi won 23-17. (AP Photo/Oxford Eagle, Bruce Newman)

Mississippi wide receiver Ja-Mes Logan (85) celebrates with fans following a win over LSU at Vaught-Hemingway Stadium in Oxford, Miss. on Saturday, October 19, 2013. Mississippi won 27-24. (BRUCE NEWMAN)

Stephen Patrick Roberts carries the U.S. flag as he leads the Rebels onto the field to play Troy, at Vaught-Hemingway Stadium in Oxford, Miss. on Saturday, November 16, 2013. Ole Miss won 51-21.

Vaught-Hemingway evolved in the process, reflecting a more inclusive environment for fans on both sides of the ball. Further expansions raised the crowd capacity to nearly 65,000, making it the largest stadium in the state. Jackson and Memphis are no longer the de facto playing fields for top-tier opponents as Ole Miss boasts one of the most popular game-day experiences in the SEC.

From its beginnings as a wooden grandstand in 1914 to its modern-day larger-than-life presence as one of the most revered places on campus, the Vaught remains the church in which members of the Ole Miss faithful return year after year to praise and worship as a collective fan base.

Even when the day’s sermon might not be what they want to hear, it doesn’t stop them from coming back for the next game.

They know on any given Saturday, God just might be on their side.