BY B. BRIAN FOSTER, PH.D.

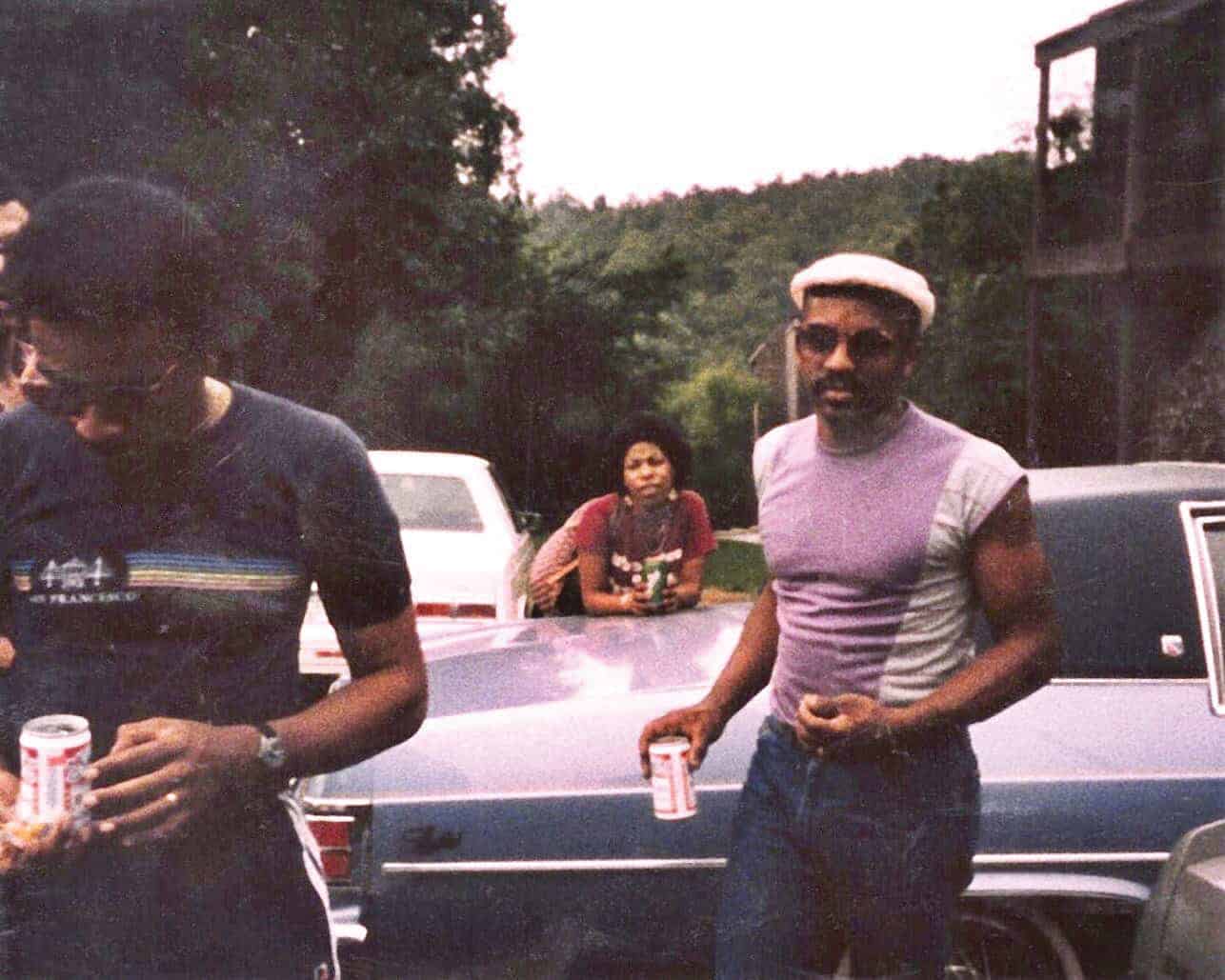

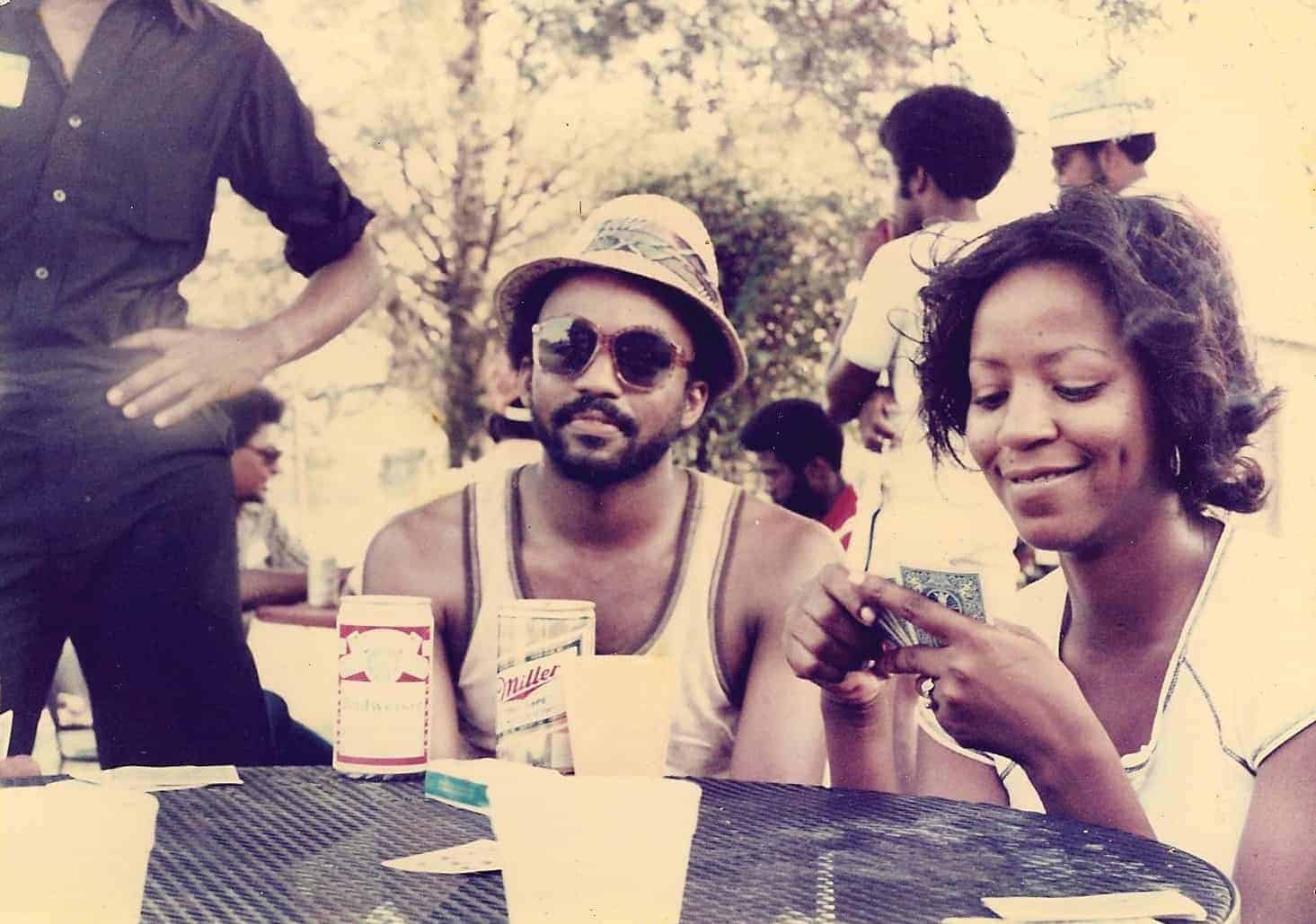

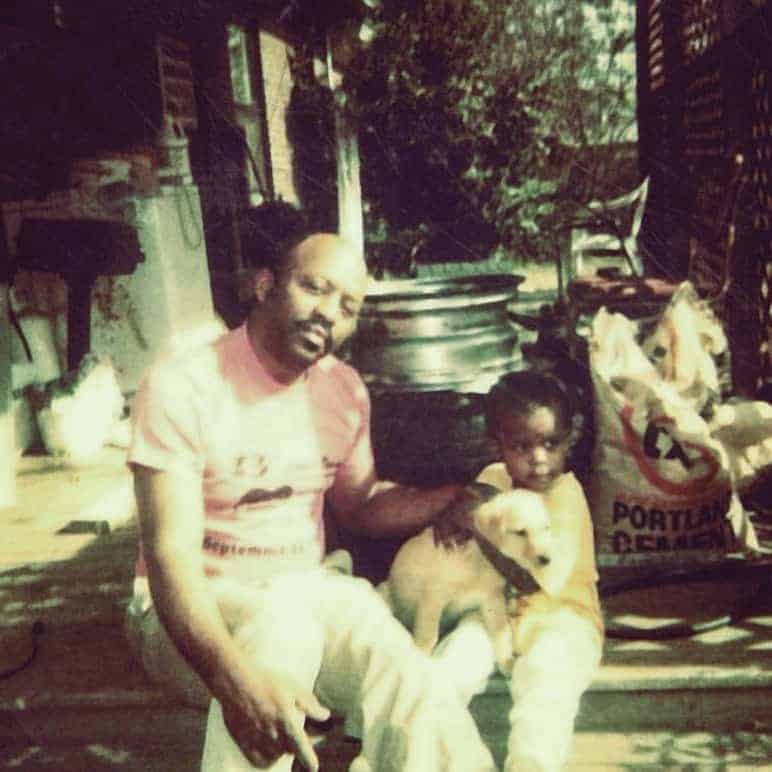

PHOTOS COURTESY OF B. BRIAN FOSTER AND OXFORD EAGLE

Daddy was a blues man. He didn’t wear suits or play guitar, but he liked to listen to folk who did—liked listening to them so much that when he got his brand new Bose sound system in 2006, he set Bobby “Blue” Bland’s Live from Beale Street to autoplay every evening at 5:30. Five-thirty was usually when his work day ended, was usually when he dragged into the house with mud or paint caked to his shoes, a red carpenter’s pencil wedged behind his ear, and his shirt halfway undone. He didn’t ask for much, just that everything in his orbit—his family and his things—be his and only his. He wanted it all to himself; sometimes didn’t care what damage he caused to keep it all to himself, and if all else failed, he had the blues.

Five-thirty. The horns always came in early, loud and clear enough that you could almost see Bobby Bland’s beige suit and maroon tie, sweat beading down the nape of his neck, before he appeared on stage, coaxing the Memphis audience with his whispered croons and trademark “squal.”

“If you’re gonna walk on my love, woman. The least you can do is take off your shoes.”

Every day at 5:30.

My daddy was a blues man, and, for a while I was too. For the most part, I liked who he liked—folks like Bobby Bland and Johnnie Taylor. But, after moving to Clarksdale, Mississippi to collect interviews for my doctoral dissertation, my opinion of the blues shifted. Between the festivals, concerts, and open mic nights, there were something that rung hollow about the music that my dad had loved so much; so I decided that I did not like it. I was sure of it—so sure that the more I lived and worked in Clarksdale, the more careful I was to remind myself that I was “not studying the blues.” I sent it in text messages to myself, typed it in my notes and research memos, scribbled it, usually in barely legible cursive, in the margins of notebooks and on the backs of business cards.

“Not studying the blues.” No, while seemingly everyone else came to Clarksdale for the blues, I was there to tell a different story—a story that, to my mind, was more timely and important than yet another commentary on Muddy Waters or Robert Johnson.

Recently, while reading through some of my notes from my time in Clarksdale, I was humored to find what had become my trademark—“not studying the blues”—written in a thin trail of black ink, bookending a string of descriptions from my first time visiting the town’s Juke Joint Blues Festival. I had written things like: “lots of blues singing—sidewalk shows, black bluesman in a blue, velvet suit singing in front of the Paramount. Not studying the blues.” There was a note about paraphernalia collectors and street vendors: “harmonica keychains. Big painting of B.B. King. Not studying the blues.” I had even noticed the food: “Funnel cakes and cotton candy. Delta Tamales. ‘Muddy Waters Root Beer Float.’ Not studying the blues.”

I found more descriptions in a second notebook—descriptions taken from my second year visiting the Juke Joint Festival. I still did not like the blues, and I still stubbornly proclaimed that I was not studying the blues, but the size and popularity of Juke Joint intrigued me.

Named for the small entertainment halls that once served as hubs of black southern commercial and entertainment life in towns throughout the Delta, the Juke Joint Festival was, and remains, a staple of Clarksdale. Since its inaugural year in 2004, it has grown into one of the largest blues festivals in the region, bringing blues acts, street vendors, and thousands of blues fans to town each April.

“Our biggest export is blues.”

“The first year we had five or six, no more than half a dozen juke joints and clubs involved with the night time portion (of Juke Joint Festival),” festival co-founder Roger Stolle recounts the rapid growth of Juke Joint in a recent interview with the Clarksdale Press Register. “Today, we have 20 nighttime venues and 12 daytime stages…over 100 acts performing…visitors from 23 foreign countries and 46 states.”

As Stolle notes, Juke Joint has become Clarksdale’s most popular social event, a development welcomed not only by the scores of blues fans who make the pilgrimage each spring but also by local elected officials, business owners, and some residents.

“Our biggest export is blues,” notes former mayor Bill Luckett in a brief conversation. “With events like the Juke Joint Festival, visitors come in and spend their money here, and that’s very helpful.”

“The Juke Joint Festival has undeniably been one of the greatest catalysts for the growth of our tourism industry,” writes native resident Nathan Duff for the Press Register. “(Juke Joint) works. For over a decade now, it has brought thousands of people here, and most of them wind up coming back. Some have bought homes here. Some have opened businesses downtown. Some simply come back year after year, and spread the word in their own hometowns around the world about how cool Clarksdale is…”

“Clarksdale is the blues,” local resident Grant Jacobsen brags to me in an interview. “It’s our heritage. In a place where you hear a lot about the bad, the blues is something good for us to show off.”

Beyond its size and popularity, there was something else intriguing about the Juke Joint festival: its racial demographics. Alongside my descriptions of the festival’s performers, street vendors, food, and games, I had noted something else: “Very, very few black folks. Where are the black folks? Not studying the blues.”

Indeed, throughout my time in Clarksdale, I had been puzzled by the lack of black attendees at festivals like Juke Joint and, more broadly, at blues-related events around town. So, I decided to do what, to me, seemed a strange thing—a thing that I had reminded myself, time and again, that I had not come to Clarksdale to do: study the blues. Rather, than resist the town’s blues history and avoid local blues scenes, I decided to lean in and pay attention. I wandered into every blues club and juke joint in town. I visited blues museums, historic sites, and specialty shops. I asked nearly 200 residents whether they liked the blues, how often they attended local blues clubs and festivals like Juke Joint, and what they thought about blues tourism in the area. And, after more than a year of wandering, and visiting, and asking, I learned that my mantra of “not studying the blues” was not just a description of my initial research interests. Rather, it could be applied more broadly to the views that many residents, especially black residents, held toward the abundance of blues tourism in town.

“I don’t like the blues.” Doris King, a 71-year-old native resident, informed me with little hesitation. “It saddens me.” While she referred frequently to the social and economic potential of the blues, she expressed a deep skepticism about whether that potential would have a tangible and long-term impact on local black communities. She was not optimistic. “The blues just won’t keep us standing.”

Like Doris, Vera Ann Johnson, a 52-year-old native resident, acknowledged the commercial and economic potential of blues tourism in Clarksdale while remaining largely pessimistic about its long-term viability. “The thing, what they’re doing with the blues is alright—I have no problem saying it’s got some potential—but what I always say, too, is that it can’t be too particular…It need to help all communities equal.”

Other black residents were equally skeptical, if for different reasons. Rick Sutton, a 45-year-old native resident, explained the absence of black residents at blues events like Juke Joint. “We are more of a southern soul blues type of people. Let somebody come and put on a show like that. We’ll patronize that…but not these festivals and things. That’s more for them than for us.” Rick was joined by a chorus of black residents bemoaning the ways that the blues had been “taken over” by white residents, “foreigners,” and tourists.

“They not living the blues like we lived the blues, like we living the blues.” Essie Dee Lyles, a 52-year-old native resident, explains. “The blues came out of that time when we was…just ‘schooching’ by. The blues came from that. When they play the blues, it just ain’t real. You can hear it. It just ain’t real.”

“The blues just won’t keep us standing.”

The more I considered how black residents like Doris, Vera Ann, Rick, and Essie Dee were describing and dismissing the blues, the more it struck me that they did not dislike the blues as much as they disliked how the blues was played and leveraged in Clarksdale. Like Essie Dee, many of them remembered living the blues—and allowed that in some ways they were still living the blues—and looked upon Clarksdale’s blues scenes, especially big events like the Juke Joint Festival, as unrecognizable. The blues that they knew, whether Tyrone Davis or Jackie Neal, felt distant and disconnected from what they saw and heard in the sounds around town. And, for that reason, they were not studying the blues in Clarksdale.

It’s 5:30 in the evening—an April evening in Mississippi, so the sun is barely dim, and outside is still hot. Like clockwork, I hear the horns, then a voice: “Hello! We are the Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland Orchestra.” I am sitting at momma’s house working through the final edits of my dissertation, which now has a name—“I don’t like the blues”—while my daddy’s favorite blues record plays in the background.

I laugh at the irony.

Brian sitting with his dad at their early home in Baldwyn, Mississippi.

“You know, (your dad) was a blues man.” Momma explains to me, a preemptive to what she must have expected would be another flurry of questions about the man we had buried eight years earlier.

“I think I’m like him,” I respond. I listened to the album all the way through.

Dr. Brian Foster is a writer and scholar of race and community life in the American South. He is currently Assistant Professor of Sociology and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi.