By Julie Hines Mabus

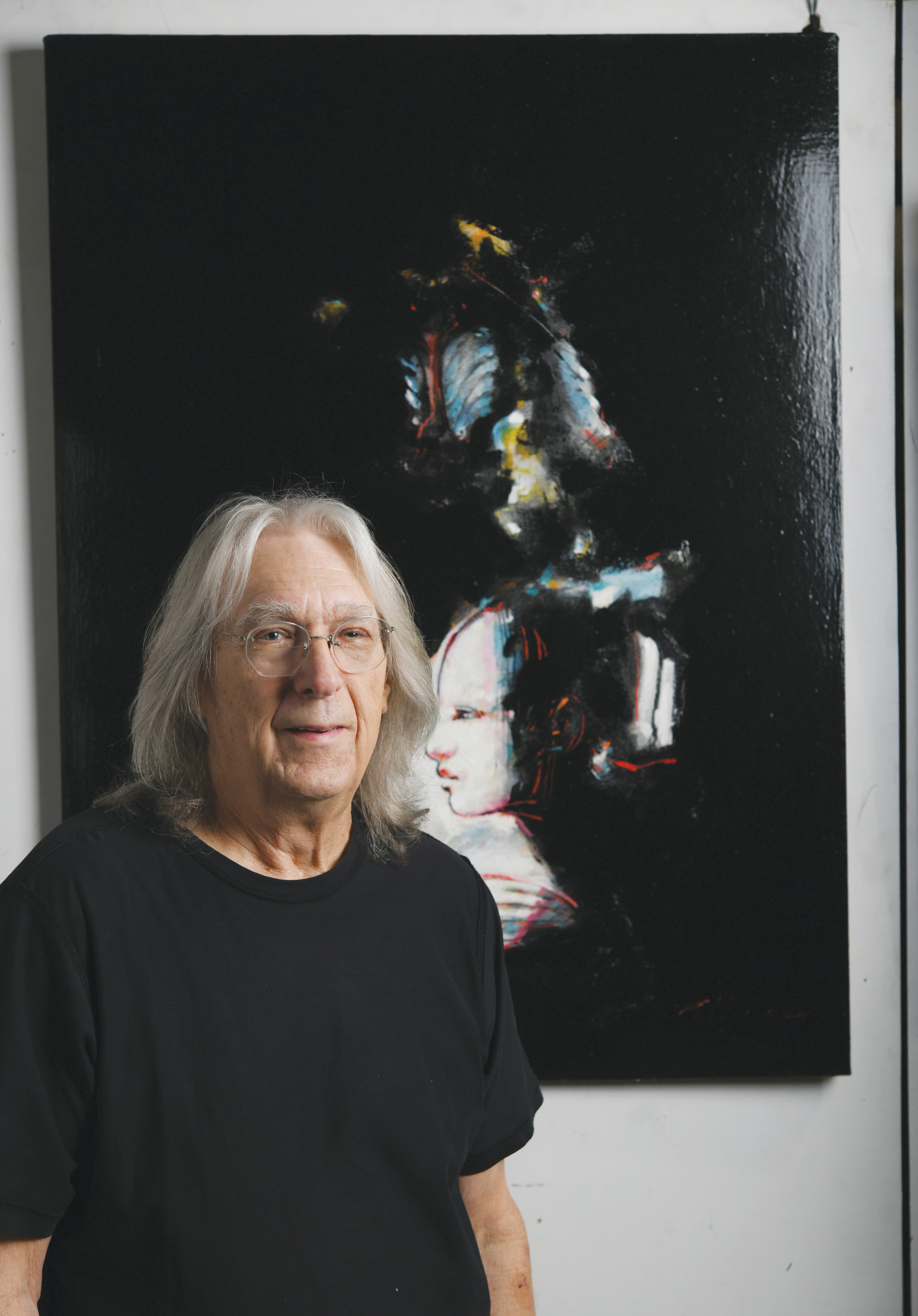

Jere Allen is a fascinating enigma. I met Jere and his wife, Joe Ann, at an estate sale some months ago. Of course, I had seen his work at Southside Gallery in downtown Oxford and knew of his unmistakable style. Recognizable elements pass through his compositions–great expanses of bold colors, often dark; bodily shapes or faces articulated through shadow and light; character groupings unknown to the outside eye but signifying much to the artist. Before we met, I had imagined him a moody, contemplative sort of fellow. Man, was I wrong.

Jere greeted everyone at the sale with a hail-fellow-well-met spirit. Before a formal introduction, we were exuberantly discussing the merits of a metal art chest of drawers as if we had known each other all our lives. He was light and funny, “full of piss and vinegar,” as my father used to say. I connected with him at once.

Jere’s studio is a metaphor for the changes Oxford has experienced in recent history. When he and Joe Ann bought the building twenty-your years ago, the location was tantamount to a country setting, hidden from South Lamar by a forest of trees and underbrush. While searching for the address he gave me, I had to drive through a hotel parking lot to find his driveway. The trees had been replaced by the hotel and a strip center. But his adjacent studio, sitting on his small but undisturbed patch of land, stood tenaciously behind and under a canopy of woodlands.

Jere freely answered my first question about his time in the Marine Corps Reserves in the 1960s. His military stint seemed counterintuitive to an artist’s spirit. “My older brother had left home and was attending Ringling College of Art in Sarasota, Florida. I knew I had artistic talent, and the military was a way I could afford the school.” That answer set the tone for the interview. It seemed every challenge Jere has faced, from his young years in Selma, Alabama, to his responsibility for a wife and two children at the age of twenty-three, to starting his career as an art professor at Ole Miss, he has faced it practically and without any rancor. I marveled at his joy of living.

From his early years, Jere had a sense of his own talent. “My grandmother was an artist, and I drew animals from her paintings. In the fifth grade, I drew this picture of a nude body. It wasn’t meant to be bawdy or lewd; I was just fascinated by the human form. My teacher picked it up, looked at it, and told me to return to my classwork. Another time, my brother brought home an “Archie” comic book. I held a page up to the light and traced Veronica–you remember Betty and Veronica–I traced her figure. It was always about the shape of bodies.”

Two professors made a lasting impression on Jere’s life and work. Fiore Custode, his first painting teacher at Ringling College, gave Jere the fire to commit his life’s work to Art. With all its probable risks, Jere’s father reacted to his son’s decision, “Whatever you want to do with your life, do it.” Amazing.

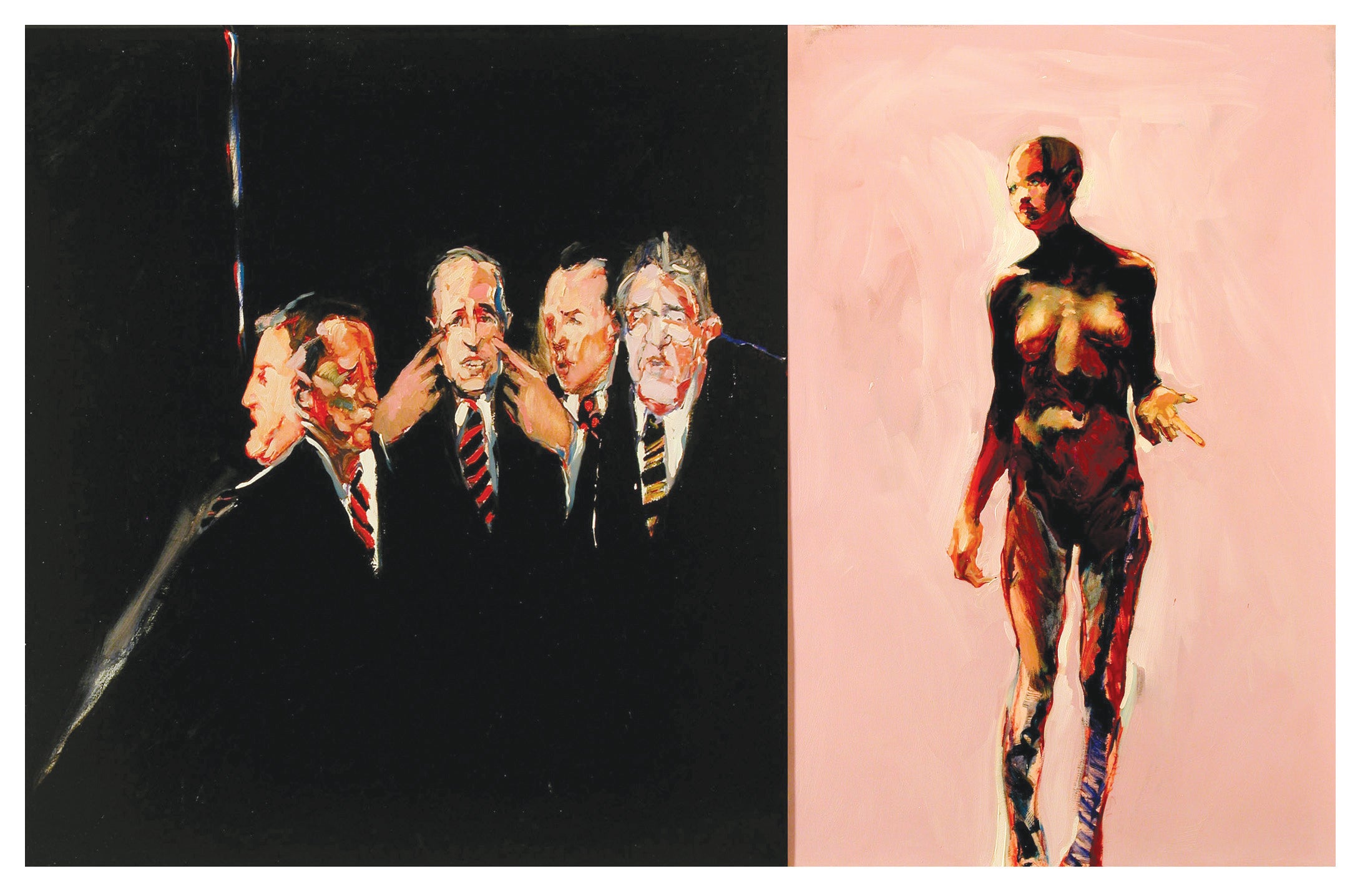

Frank Rampolla, another Ringling professor and “figurative expressionist,” was paramount in developing Jere’s natural gift for figure drawing in the 1960s. During that period, the works of pop artists like Andy Warhol dominated the market; Rampolla was an outlier. He clung to the composition of the Italian Renaissance and Dutch baroque masters as he responded to current social and political events. Like Rampolla, Jere embraced the dark side of society as he incorporated political sensibilities into his works. Jere offered, “In my early days, sometimes you couldn’t tell whose work was whose.” The similarities are profound.

In 1972, after receiving his MFA from the University of Tennessee, Jere brought his family to Oxford, where he began a long and illustrious career as a painter and painting professor at the University of Mississippi. He painted in his off time, every day. “Painting was my research. It was a way to break away from my teaching and find new energy in the discipline.”

Jere’s body of work is not easily understood at first blush. But the viewer immediately gets the passion and intensity. On his website, he explains, “My paintings employ a reactive method in the search for an elusive notion that has perplexed me for years. The images, symbols, and composition that stem from personal, social, political realities are often a foil to assist in the realization of feelings generated by that evasive notion.” I was not going to let him get away with that statement without some explanation.

While Jere spoke of his work, his “reactive method in the search for an elusive notion” began crystallizing. “I got on a tear of drawing faces, all black and whites. I spent a whole year just drawing faces. My friends, my mother, my wife, all just faces. In the 90s, it was art dogs, one painting after another.” Were these just repetitive, albeit unique works, or his “reactive method in the search for that elusive notion?

“I did a whole series of people looking at things. I would paint the symphony, but the instruments or the setting was not the subject. I wanted to capture the people who were there experiencing the symphony. It was all about the spectators; what were people gathering to look at? That’s what I wanted to capture.”

“Perhaps the elusive notion for which you search is life itself.” I offered.

“No. I Haven’t found it yet. It’s a feeling. I do the same thing every day. All I know is I come down here; I’m trying to find out what is gnawing at me, making me put that first mark on a canvas.

“When my children were small, I drew incessantly for them as I put them to bed. I tossed the sketches on the floor, and we all walked on them; they were just lying there.” Jere led me to one of his art cabinets. “It drove Joe Ann crazy. She started collecting them here, in these drawers.” Layer after layer spilled out. Those children grew up in a household totally emersed in Jere’s work.

Though he shows his work at Southside Gallery, Jere’s main marketing effort has been through the Carol Robinson Gallery in New Orleans. “Years ago, I approached Bryant Allen (of Bryant Galleries in Jackson). He gave me some wise advice, ‘I’m not going to be able to sell your work here. The two best art markets in the country are New York City and Los Angeles. But New Orleans is hard to beat–it’s right in the middle.’ I didn’t feel good about his advice, so I tried a gallery in Los Angeles. I learned the hard way; the only way to deal with selling is to be near the gallery. You’ve got to powwow, build a network. I found Carol’s gallery in 1989 and have been there ever since. Anyway, my last series of work was paper boats–that was at Carol’s.

“All the paintings started with a paper boat. I did so many paintings of paper boats. Paper boats are a metaphor for life; boats taking you to the other side, rowing toward a light.

Jere segued momentarily. “E. M. Forster wrote a short story, “The Point of It,” which is an interesting comparison between the lives of the two young men in a row boat. They’re trying to get to the other side. And there are those casino boats…the ship of fools.” He paused, then smiled. “It’s like a psychopomp.”

“A what?”

“You know, it’s from the Greek. They are the guides that convey the souls to the other side, like boats.”

He continued. “What makes me stand in front of the canvas? What gives me the incentive to put the first mark on the canvas, just a little gesture. The whole painting stems from that mark.

Jere stood silent for a minute. “Bill Russell, a great basketball player, said, ‘I practice until I can react naturally to any situation.’ That’s the way I want to paint. I want to reach the point where my work is strictly uncontrived. No overthinking.”

“I know your work has reflected social and political upheavals. Let’s talk about that.”

Jere opened a book to his painting of a nude woman, her body suspended in time and space. On the same page in the book, a portrait of five men was juxtaposed against the nude. The men’s faces eerily came out of the page in shadows and light. He explained, “The combined work is called ‘There is no cure.’ It’s Anita Hill. The men–Heflin, Hatch, Kennedy, Biden, and Specter–were some of the members of the Senate Judiciary Committee who questioned her for the Clarence Thomas nomination for Supreme Court justice. It was rough.”

“You know, I do tronies; I don’t do portraits.”

“OK, you’ve got me again.”

“It’s an ideal. It’s in Flemish Baroque painting, an exaggerated facial expression.” I immediately thought of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring. “That’s the way I paint faces.

“But this lady came to me some years ago. She wanted a portrait of her baby girl. ‘I didn’t do portraits,’ but she persisted. When the child was four, I acquiesced. ‘I’ll use your child as a model. But that’s the best I can do. If it works, it works. You can’t ask me to do anything to change it.'” He showed me a photograph of the painting. It was beautiful, almost surreal.

In reality, Jere’s studio is an art museum. For every painting he has sold, and the list is overwhelming, a multitude of his work is leaning against walls, hidden in corners and cabinet drawers. He paints every day, and his work is powerful and speaks to our times. He has been shown in exhibitions worldwide, his work marks the pages of many exquisite books, and his honors are almost boundless like his body of Art.

He keeps searching, searching for that elusive notion that has perplexed him for years. Perhaps he is that notion, driving us to an unknown level of understanding about the world that surrounds us.