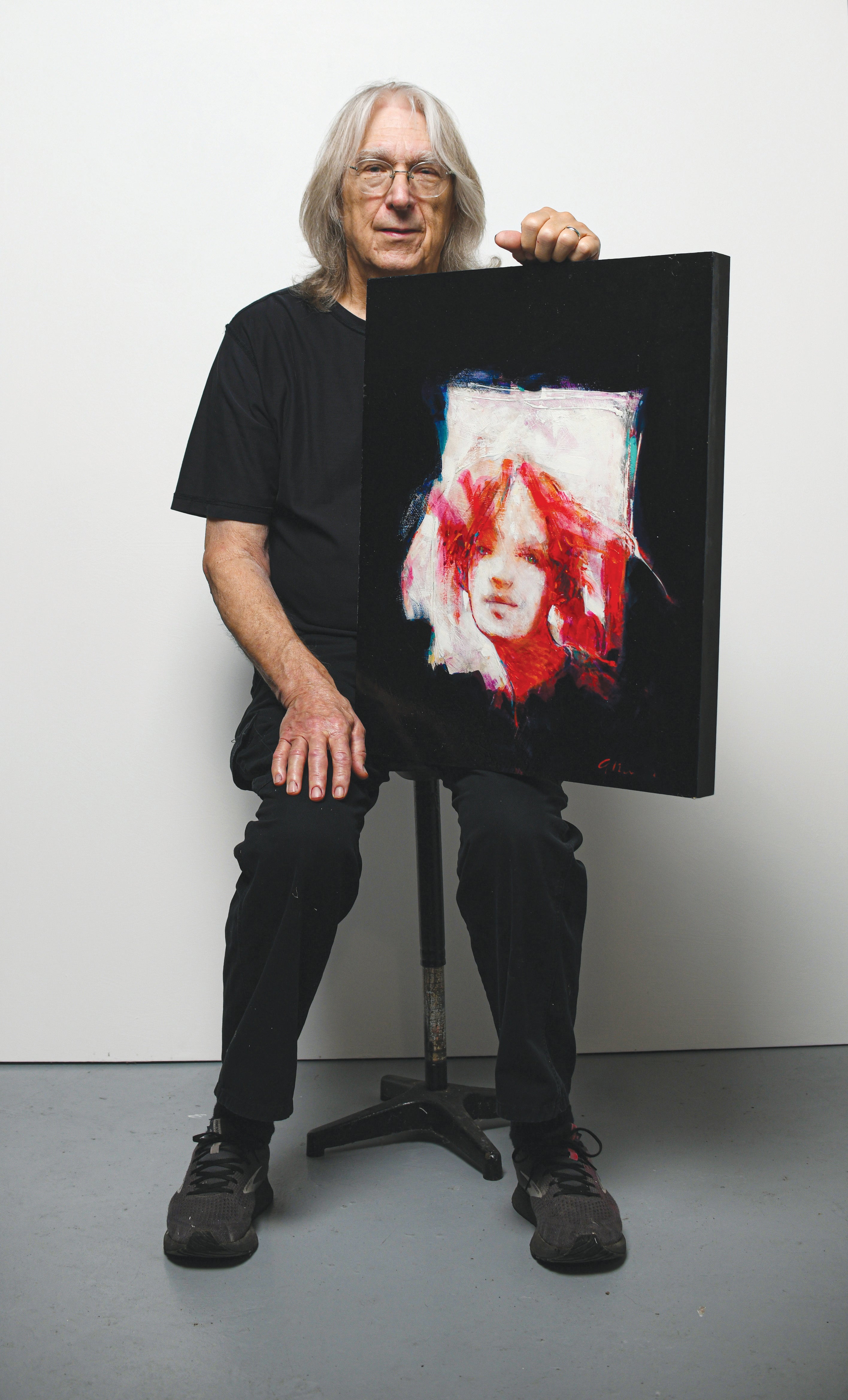

Vivian Neill at Treehouse Gallery in Oxford, Miss. on Thursday, October 24, 2024. (©Bruce Newman)

I have often wondered about handsome men who rely on their good looks, frequently shirking their family responsibilities. What is the emotional impact on those family members who love and depend on them? This question resurfaced when I recently visited with an extraordinary woman, Vivian Pigott Neill.

Jim Pigott, a devout Roman Catholic born in Chicago in 1922, was the archetypical handsome man. He married Zita, an immigrant from a small Austrian village, and they raised six children. While Zita cared for the family, Jim’s striking good looks probably contributed to a pattern of emotional neglect toward his loved ones.

Yet neglect need not be fatal. In the case of Vivian Pigott Neill, Jim and Zita’s fifth child, neglect was something she sublimated throughout her early years. But she always fought through the neglect with her artistic impulses—pencil drawings, pen and ink, collages with scraps of paper—these were her survival weapons.

Although Vivian and I both hail from Jackson, she grew up in the Catholic community, and I am five years older. I have often felt like a galumphing springer spaniel around her; she was so Audrey Hepburn in looks and style.

I met Vivian in the late 1980s when she and her then-husband Malcolm White and his brother Hal owned and operated the infamous and fabulous Hal & Mal’s, a nightclub/restaurant in downtown Jackson. Malcolm was the face of the establishment, while Vivian managed the underpinnings—keeping the books, checking on customers, and ensuring the trains ran on time. But few knew of her artistic talent.

In the Pigott family, the “artist” label has long been associated with Vivian’s older sister Carole, who once had a studio in a warehouse space connected to Hal & Mal’s. Carole died five years ago in Sante Fe on the eve of her first museum show in Marietta, Georgia. Vivian spoke of Carole’s work and her museum show with the highest praise.

This is Vivian—always and forever promoting other people and their works. It was my mission to chip away at that multi-layered defense. Her story is amazing. Vivian began. “Growing up, I lived primarily in the Catholic world, attending their schools. It was very insular. Somehow, I convinced my parents to let me transfer to Jackson Prep my senior year. Before that, I never knew any of the Jackson social stuff existed, like the Junior League. It was a real eye-opener for me.”

Vivian began her freshman year at LSU. “I wasn’t focused on academics so much. Art was all I wanted to study.” But she didn’t graduate from LSU. Between semesters of her junior year, her father pulled the college funding. She moved back to Jackson and started working at George Street Grocery, a downtown music venue and restaurant. “That’s where I met Malcolm.”

“Initially, George Street gave me the flexibility to pursue my art. I was experimenting with natural dyes and different papers, collages, pen and ink, that sort of thing. But I was always good with numbers, and Malcolm encouraged me to focus on the business side of George Street. I kind of got locked in; as we took on other projects, I got more involved in the business end of things. My art took a back seat.”

After several years, Vivian and Malcolm got married and in 1987, they opened Hal & Mal’s when their daughter Zita Mallory was two years old. Once again, Vivian’s art was sacrificed to the overwhelming responsibility of raising a child and managing the business.

Eventually, the couple bought a house in Grayton Beach, Florida, and took a year renovating it while planning to expand their restaurant business to Oxford. Vivian and their daughter Zita spent long periods of time in Florida, and the separation led to pressures in the marriage. In the end, Vivian and Zita stayed in Florida for five years. The marriage eventually dissolved.

As a single working parent in Florida, Vivian faced a paradigm shift. For perhaps the first time, she began to think of her art without the constraints of professional responsibilities. In 2000, she returned to Mississippi, settled Mallory in the school system in Oxford, and began taking art classes at Ole Miss. Twenty-five years after Vivian left LSU, she was on her way to earning a Bachelor of Fine Arts. “When I was at LSU, it was total immersion into the art world. I was intimidated. And I avoided all the academic courses I could. But when I came to Ole Miss, I loved them. Besides art classes, I took a lot of history.”

Vivian eventually married Walter Neill. Together, they started Oxford Treehouse Gallery, located southeast of Oxford, and live in a stunning house Walter hand-built on the property next to the gallery.

“In the fall of 2003, my last semester, daughter Zita started her first semester at Ole Miss.” Vivian’s words were laced with pride. She had accomplished a remarkable feat against a lifetime of barriers. She clearly extended that pride to her daughter.

To obtain her degree, Vivian was required to complete a graduation thesis. She relied on her Catholic upbringing to develop the theme for the project. In the Catholic world, August 15 is the Feast of the Assumption, the day the Virgin Mary’s body is assumed into heaven. It also happens to be Vivian’s birthday. On that day in 2003, a cocoon unraveled.

Though not a devout Catholic, Vivian acknowledges the significance of the Virgin Mary. Drawing from The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd, & Mary Day; is a celebration created by the Boatwright sisters to honor the Black Madonna, whom they called & Our Lady of Chains; The Black Madonna symbolized strength, resilience, and hope for the female characters in the book.

On August 15, 2003, Vivian created her “Mary Day and invited an intimate group of female friends. The invitation itself was a piece of art, including Vivian’s original block print of a broken chain, highlighting the importance of “Our Lady of Chains.” Her homage to “Mary Day” also told the story of Vivian’s survival. Vivian’s oil paintings from the celebration documented the event and eventually hung in the Bryant Hall exhibition room for her graduation thesis.

On that monumental day, the ladies gathered at the Neill’s land. Vivian had made white veils, which hung from the branches of a nearby tree in anticipation of the event. Each participant put on her veil, an expression of a childlike, virgin spirit. The ladies were given cards with gunpowder. Each wrote down what she wanted to release.

The group then processed through the backwoods. This would be Vivian’s time of breaking barriers, regenerating a life, and reviving a holy woman who was “complete and whole unto herself.”

The day would not have been complete without the Lady herself and her donkey. Vivian had constructed a papier-mâché likeness of Mary. The ladies carried the statue, and the Jones Sisters, a local musical group of four women of color, led the procession in song with the donkey and the Mary in tow. When the group reached what Vivian calls “the point where two creeks come together,” the women tossed their loaded envelopes into a firepit, sparking a symbolic release of unneeded worries and burdens. At the same time, the Jones Sisters sang “Mary” by Patty Griffin.

When the procession returned to Walter’s workshop, dining tables were set and ready to receive the group. Walter and several male friends attended the women as they ate gumbo and drank champagne.

After I heard Vivian’s story, I studied the photographs of the paintings again. I wanted to cry. I once watched a Monarch escape from its cocoon, and it felt the same. I had no words.

Walter had originally built the structure of Oxford Treehouse Gallery as a studio for Vivian. True to Vivian’s nature, she expanded it into a space to include other artists to show and sell their works. “You know, I’m not a great self-promoter,” she said, summarizing the modesty of her soul.

Today, Vivian has a small studio at home. “Walter gets excited when he sees me painting. Sometimes, I go outside and paint the surroundings, landscapes, maybe—just to appreciate where I am at that moment. It’s like meditating.”

As I write, Vivian is in France with her eight-year-old granddaughter, Wren. “We’re not going to rush around. We’ll be in Paris for a while and then to Avignon. I’m taking an art book with watercolors and gouache so we can paint when and where we are—paint on our laps.” Vivian explained that gouache is a watercolor medium, but the colors are thicker and more intense.

This trip once again represents her soul, her persona—always doing for other people. I cannot wait to see the work she produces on her trip. I will insist on buying one of the new works. I hope she will allow it.

By Julie Hines Mabus

Photos by Bruce Newman