BY ALEC HARVEY

Rick Bragg has written a cookbook.

But in the hands of the Pulitzer Prize-winner who has detailed so vividly his small-town Alabama roots in books such as All Over But the Shoutin’ and Ava’s Man, you know it won’t be your ordinary cookbook, as evidenced by the answer Bragg got when he asked his mother where she got her recipe for chicken and dressing. “She said, ‘Well, hon, it goes back to the time that Sis shot her husband in the teeth.’”

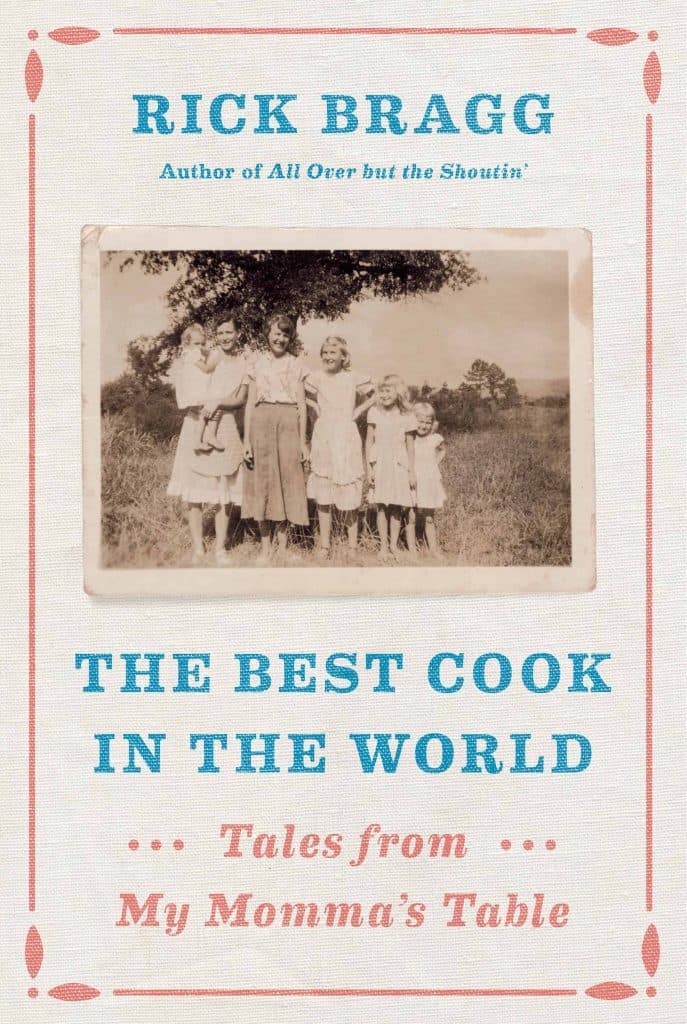

That story (and recipe) are a part of “The Best Cook in the World: Tales from My Momma’s Table,” which comes out on April 24, a day after his momma’s 81st birthday. Bragg will be at Square Books signing the cookbook on May 5 at 5 p.m.

You’ve written a number of memoirs, as well as books on Jerry Lee Lewis and Jessica Lynch. Why the cookbook?

This was one of those things that just kind of made sense. Mama was diagnosed with colon cancer. Not only did she have to undergo a massive surgery, she had to do a year or so of chemo, so we had a lot of time over the past few years, just me and her, in hospital rooms and rehab centers. I was in her kitchen one day when I had come home to get some clothes for her. Her kitchen usually smells like cornbread, like bacon grease, like collards, and almost always has a pot of something on the stove. That day, there was just nothing. I knew that not only were the recipes all locked away in her head, but many of the stories.

What was your mother’s reaction?

I said from the very beginning I wanted the title to be “The Best Cook in the World,” and that really bothered her. She said right away, “I wasn’t even the best cook on our road. My mama was a fine cook and your Aunt Edna was a fine cook.” I just told her that calling it “The Third Best Cook on Roy Webb Road” doesn’t sing.

Did you have a favorite dish your mother made while you were growing up?

Yes, and it probably has the best story. My grandma, Ava, couldn’t cook, and she was strong-willed and mean-spirited at times. My grandfather, who married for love, was starving to death. Her food didn’t have any taste or flavor, all of those things that make Southern cooking good. My great-grandfather, Jimmy Jim Bundrum, had been hiding in the mountains of north Georgia for a killing, but he was a great cook, so my granddaddy, Charlie, got on a grey mule and found his father and brought him back. War commenced. This was a fire-breathing man, and he and my grandma did battle. Over time, not only did he teach her, but they became close friends. One of the first things he taught her was ham, hambone and ham fat and trimmings cooked slowly with pinto beans. Ham and beans, basically, but I can’t tell you how good it is when my mama makes it.”

How important are the stories, such as Sis Morrison getting mad at her husband and shooting him in the teeth?

The stories were easy. In journalism there’s a phrase called “dog’s breakfast” – everything that is left over — bits and pieces of things that never had a home. I’ve mentioned food in all my books, but the crafting of it I didn’t have the skill to do it. The only way I could do a food memoir or anything approximating a cookbook was to rely heavily on the narrative, the stories behind the food. These stories go from the late 1800s to present day. It’s an epic in the most humble way I can use that word.

What was the toughest part about writing the book?

The recipes. I am not a cook. I set the house on fire almost one time with a grilled cheese sandwich. And my mother had no written recipes. She has never held a cookbook in her hands. The recipes are all from ghosts, and if you remove the ghosts, there are no recipes in my family. When she cooks in the kitchen, there are ghosts at her elbow. I’d ask her how much, and she’d say, “I don’t know.” How long do you cook it? “You just know.” How do you know? “You just know by the smell.” I don’t know if I got it right or not, but I got as close as I could with my meager skills. I think I duplicated the recipes, but if it doesn’t taste quite right, y’all have my apologies.