On Food, Family, and Finding a Way to Go On

In the wake of two tragic deaths within Oxford’s restaurant community, local restaurant owners and staff came together to mourn, pitch in and support each other as family.BY JENNA MASON

In late February, Jayce McConnell, bartender extraordinaire who got his start at Snackbar, hosted a pop-up cocktail event at Saint Leo. The restaurant had just been nominated for a James Beard award, so I made plans to stop by for a celebratory cocktail. By mid-afternoon, I sat at the empty bar with a rye old fashioned, gutted. I watched bar manager Joe Stinchcomb fight tears while he and Jayce prepared for the night.

We had just learned that one of Saint Leo’s finest servers, Eric Shepherd, had passed away early that morning due to complications from a blood clot. Eric—Shep to friends and loved ones—was a rare soul, beautiful and kind, gentle and wildly creative. He had worked at Saint Leo since day one.

By sunset that Monday, nearly every member of the Saint Leo staff joined the crowd in an impromptu gathering reminiscent of an Irish funeral. In the coming days, on balconies and at bars, members of Oxford’s service industry would drink and cry and smoke and hug their way through the first of many long weeks of mourning. We would remember Shep that Saturday in a moving celebration at the Lyric Theater that showcased his art, fashion and poetry. Fifteen days later, we would hear news of Henry Miller’s passing.

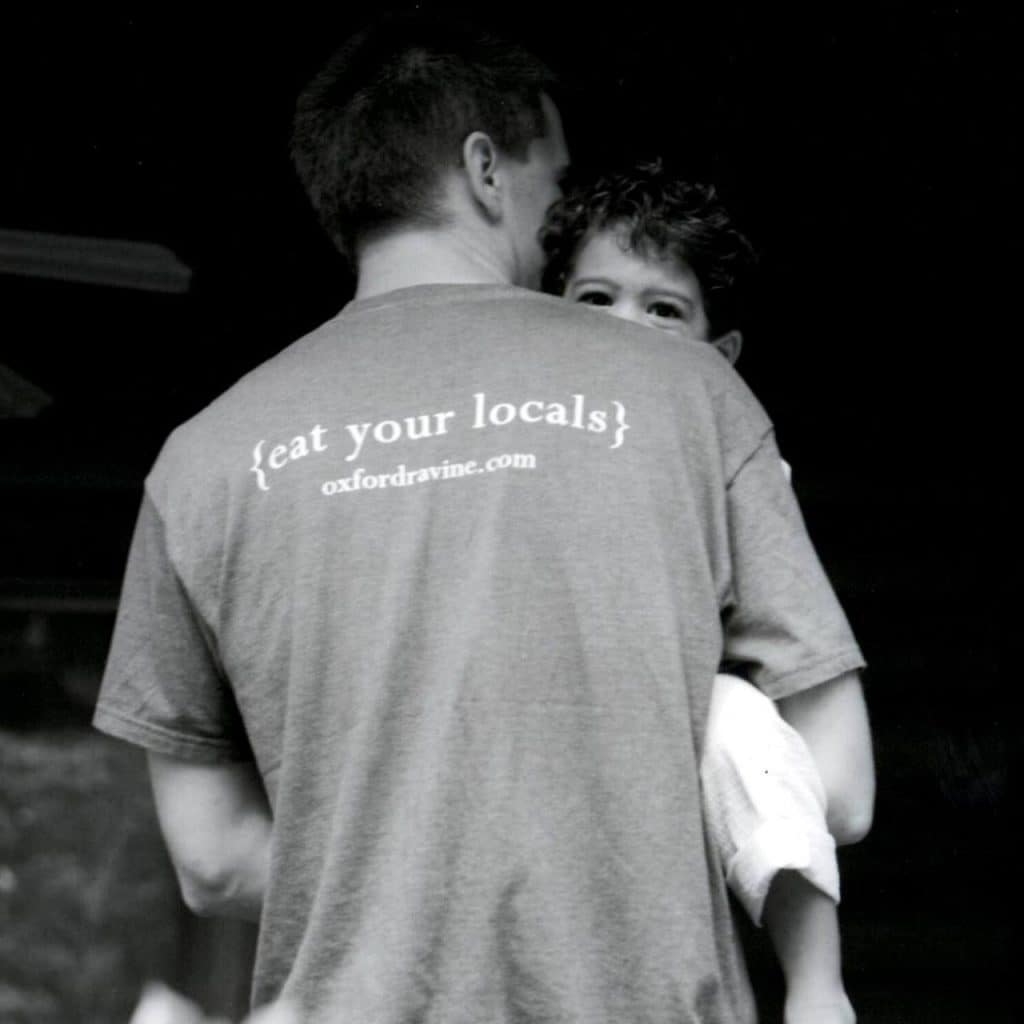

Henry Miller was the 9-year-old son of Cori Benefiel and Joel Miller, chef and owner of RAViNe. Longtime patrons remember Henry resting on Cori’s hip during service in the early years of the restaurant. I remember him at eight, helping me run plates of duck breast and wild rice pancakes to customers who melted at the earnestness he brought to the table.

Sunday mornings at RAViNe, Henry and his little brother Louis would pick at pancakes and bacon and each other while they watched cartoons at the bar before brunch service. No matter how the servers tried to hide them, the boys would inevitably discover the Shipley’s doughnuts then-bartender Mason Payne always brought in.

Cori describes how the RAViNe family has always intertwined with her own:

RAViNe has always been about family. Our family of course—if you look between the little hand sink and the dessert cooler in the kitchen, you will find etched into the concrete on the floor: All for Henry, 2007.

It has always been a family for lots of young people too, all students at one time, working hard to make ends meet, trying to figure out who they want to be, what they want to do, looking for a home away from home. Joel has spent many a late night listening and counseling kids hooked on drugs and alcohol, spiraling out of control through endless cycles of self-destruction.

We remain in touch with many of the employees who have come and gone.

When news spread about Joel and Cori’s loss, those same employees showed up, uniforms in hand, ready to work and help. It wouldn’t be the first time they’d chipped in a little extra.

Cori remembers one dishwasher, Darqula Goolsby, who used to hold Henry as he washed dishes: “Amidst all the spraying and humming of the machine, Henry at a-year-and-a-half would fall asleep in Darqula’s arms.” Another server, John Hasie, once found Henry out in the RAViNe parking lot washing his parents’ cars after climbing out of his crib at naptime.

At the restaurant’s annual Christmas party, staff would often “put money in the wine buckets (tip jars) Henry routinely put out at the annual Christmas parties, hoping to get paid for dancing on top of old crates or fudging his way through a song.”

“Not every person who has come to RAViNe has fit this mold,” Cori explains, “but the ones who have—they are our family. We all grew up together. We all continue to grow together. Henry and Louis, they are the glue. Ask any of these people, they will tell you.”

I come from a long line of restaurant lifers. In the decade or so that I didn’t wait tables, I missed it terribly. I had a career and a family, yet I would grow nostalgic as I sipped coffee at Bottletree and caught glimpses of servers rolling silverware and racking glasses.

It wasn’t the side work I missed. It was the industry camaraderie, the sense of belonging to a second family like the one Cori describes. The hospitality industry brings people together—the people receiving hospitality and, perhaps more so, the people providing it.

If you want to know someone well, work beside him or her in a restaurant.

Amid the pressure and occasional pandemonium, individuals’ true colors surface. You learn their work ethic, how they communicate, how far they’ll go to help someone out, how they handle stress and mistakes, both at work and in life.

You learn to recognize their game faces, the masks they wear when they’re struggling and exhausted—sometimes devastated by loss—but they have to perform regardless.

Recent weeks in Oxford’s service industry have made one thing clear: that camaraderie comes with a cost. All those unremarkable moments—the cigarettes smoked by the back door, the shift drinks downed during football season, the doughnuts hidden from sugar-seeking children—those are the places where you most feel connected and where you most acutely feel loss.

Still, I believe, it’s a risk worth taking. The hardships cement the friendships forged behind the kitchen door. Ask any of these people—they will tell you.

JENNA MASON is Oxford Magazine's monthly food columnist and a digital editor for the Southern Foodways Alliance.