Andi Bedsworth—An Inexhaustible Voice

By Julie Mabus

Photos by Bruce Newman

Writing a detailed story about a person’s life is not a superficial activity. It requires a deep dive into the person’s persona. And interesting things rise to the surface during the process.

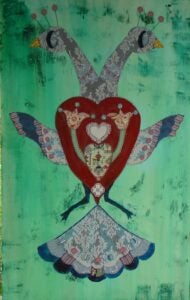

My deep dive with Andi Sherrill Bedsworth began as I approached her home west of town off Highway 6. Colorful textile creations, hanging in her flower bed and on her front porch, marked the spot–tangible outpourings of her love of fabrics and thread.

We settled in her studio with its myriad stacks of transparent containers holding colored materials and threads, and her story unfolded.

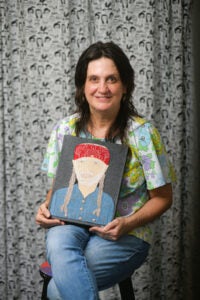

And Bedsworth in Oxford, Miss. on Saturday, June 15, 2024. (©Bruce Newman)

One of three children, Andi was born in Texas, but her parents, Michael and Mary Ann Sherrill, moved to Baton Rouge when she was three. “Dad was a die-hard Texan. He really was one of those people who believed that Texas was a whole other country–and the best country in the world, you know? But Mom’s heart was in Louisiana.”

Andi’s thoughts wandered off for a minute. “Dad was a systems analyst, a computer programmer. He was brilliant.” Her parents separated when Andi was ten, and he eventually went back to Texas. It’s where his heart was. He stayed there until he died.”

“What was it like in Baton Rouge when you were growing up.” I didn’t expect her response, but it aligned perfectly with her whimsy.

“It was hilarious. It’s like wet there, and it rains all the time, and it floods, and it’s hot, and there’s hurricanes.” Andi described her childhood almost entirely in the context of the hurricane season. “When I was a little kid, the flooding didn’t worry me because we got out of school. It happened every year.” Andi described her Baton Rouge neighborhood scene when the rain started, and the flood waters rose. My parents and the neighbors would sit in lawn chairs holding a cocktail in one hand and a yardstick in the other, measuring how high the water was getting. All the kids played in the street as sewer and bayou water got deeper and deeper. We had a ball.”

“I understand you inherited your sewing talent from your mother.”

“I understand you inherited your sewing talent from your mother.”

Andi began a story of her mother’s unending energy with a needle and thread. “She’s always been very creative. When we were kids, she was constantly quilting, and she made all our clothes.”

And like Bayou Manchac and the great Mississippi River—each body of water seasonally rising beyond its borders, spilling its liquid on the city of Baton Rouge—her mom’s creativity overflowed well beyond the confines of a sewing machine or needle and thread.

Andi laughed. “I mean, she was always doing craft projects. If there was an empty plastic bleach bottle, she would make a nativity scene out of it. A cardboard box from a new refrigerator might become our next playhouse.

“Then there was the time in 1976 when it snowed. It never snows in Baton Rouge. I was five, and my little brother and I had the chicken pox. Mom didn’t want us to miss the experience. She went out and brought the snow into the kitchen so we could play in it like we were outside.”

“So, your mom taught you how to sew?”

“Not exactly.”

When Andi was seven or eight, her mom gave her a Ken doll. Unlike her Barbie, who had a black plastic case full of gowns and stiletto mules, Ken came dressed in only a pair of shorts. “I think he was a Malibu Ken. I wanted him to have proper clothes so he could take Barbie on a date.

“I told Mom I was going to make him a pair of pants.” Andi’s pattern involved sewing two pieces of fabric together to make a front and a back. Then, she ran another seam down the middle to create the leg openings.

Her mom, Mary Ann, was adamant. “That’s not going to work.”

“I told her I knew it would work. It didn’t work.”

Mary Ann temporarily squelched Andi’s sewing ambitions. “You are never going to learn to sew. You don’t have the patience, and you don’t listen to me.”

Motherly good intentions gone awry, Andi stayed away from a needle and thread until her eighth-grade home economics assignment. Half the school year was dedicated to making an outfit.

Andi’s telling the story set the stage for disaster. I could feel it coming.

She built the tension. “The thing is, the pattern our teacher chose, it wasn’t hip, you know? I mean, it was like straight-leg pants. Back then, in the 80s, everything was peg-legged, really skinny. So, it looked old lady to us, you know? The blazer, I mean, what fourteen-year-old wears a blazer?”

Undaunted, Andi soldiered on through the project. “It wasn’t easy. Sewing is very technical. I brought it home, and this time, Mom was helpful; she talked me through it. ‘Just keep working at it. It will turn out okay.'”

The day of reckoning came the day the girls finished their projects. Andi raised her shoulders as she told me. “I was all excited, and I asked my friends if they were going to wear their outfits to school. They all said, ‘No!’

“I mean, we worked on that thing for weeks. Well, I wore mine to school. They all looked at me, ‘Girl, you’re wearing that?’ I guess it really did look like an old lady’s suit. I took a break from sewing after that.

“But the next year, I remember, I wanted something new to wear. I don’t know, maybe some shorts. And I thought, “I can just make it myself.”

“But the next year, I remember, I wanted something new to wear. I don’t know, maybe some shorts. And I thought, “I can just make it myself.”

That “aha” moment was practical, but a brilliant, life-changing awareness would follow. After those shorts, Andi realized she could make her own prom dress. “By the time I was a senior, I was making a lot of my own clothes, and friends were coming to me and asking me to help them sew.”

But, it also became an awakening of a creative talent that has powered her throughout her life. Somewhere along her path, the sewing machine and her needle and thread evolved into her tools of art.

The first leg of her artistic journey was costume making. Andi earned her Bachelor of Arts at LSU with an emphasis on costume design. During college, she was allowed to make costumes for the theater, but she knew her real gift would be in the design work.

As fate would have it, in her junior year at LSU, Andi’s life took a significant detour when she gave birth to a baby girl. Though the responsibilities of being a single mother were daunting, she kept her eye on her goal of designing costumes for the theater.

“When I finished college, I wanted to go to graduate school to get my costume design degree. Fortunately, I had a mentor at the time who said, ‘Andi, take a year off, work in the industry. You have a 14-month-old. Make sure this is what you really want to do.'”

Andi followed his advice. For two years, she freelanced for Swine Palace, a non-profit, professional theater attached to LSU and The Baton Rouge Ballet Theater.

“In 1995, I got the costume shop manager job at LSU, where I had studied as an undergrad. It was a dream job for me. I met Tim, my future husband, there. He was an actor and in set design. It was this perfect theater kind of life. But I always felt that glass ceiling above me; I knew I needed to get a graduate degree.”

Despite the best-laid plans, the universe has its way with us when it wants. In 2000, when Andi and her husband were expecting their first child, he lost his job at LSU. Tulane in New Orleans had an opening for the manager of the theater shop. He applied and got the job, “I had to stay at my job until the baby came, so he was commuting round-trip every day. It was a tough year. We had our baby girl during that time, my second child.”

Andi’s husband encouraged her to go to grad school at Tulane. “He knew I always wanted to go back. So, in 2001, we left Baton Rouge and moved to New Orleans. We stayed for three years while I worked on my master’s in costume design. When I graduated, he said, ‘We can go anywhere you like with that degree.’ That’s when we came to Oxford.”

“What specifically brought you to Oxford?”

“I found a job in the theater department at the University and applied for it. Plus, we had two girls, and the public school system is so good here. It’s terrible in Baton Rouge and even worse in New Orleans.”

“Tell me about your job.”

“For the first couple of years, I liked it okay, but I think once I got divorced, it became difficult.”

Andi paused, realizing she had left out a part of the story. “Tim had a brain aneurysm rupture when we lived in New Orleans. It was in 2003, my second year there. He almost died, and so they had to do emergency neurosurgery on his brain. He never was the same after that. It was hard for him.” Tim stayed in Oxford until his girls were grown but is now living in Iowa.

Andi’s position was the costume shop manager and costume technology instructor. As she described it, it wasn’t a high-level position, and she was required to teach in addition to her theater responsibilities. “So, I basically held two jobs. It wasn’t creative, and they expected so much from us. We had to work a lot on weekends and at night. I was going through a difficult time personally, and I didn’t feel any compassion from my co-workers. It was a tough environment—a rigid hierarchy and a lot of politics.

“After seven years, the University and I parted company. I was relieved in many ways because it wasn’t a creative job. I’m an artist, and the job offered little creativity. After I left, they hired three more people to fill my spot, if that tells you anything.”

During her tenure at Ole Miss, special students brightened the path. “One of my students and I used to have a radio show on Rebel Radio, the campus radio station. He was a sound design student who sometimes worked in the costume shop. We always talked about music, so we approached the station with a unique idea for a program, and they accepted it. We called it Musicology and kept it running for two years.

“We would do themes each time we were on the air. For example, if the theme was food, we would only do songs about food. Or we would do a whole hour with nothing but love songs or songs about breaking up. I remember one program was about murder. It was great fun and a special time in my life.”

And Bedsworth teaches an art camp at the Powerhouse Community Arts Center in Oxford, Miss. on Thursday, June 6, 2024. (©Bruce Newman)es each time we were on the air. For example, if the theme was food, we would only do songs about food. Or we would do a whole hour with nothing but love songs or songs about breaking up. I remember one program was about murder. It was great fun and a special time in my life.”

Andi’s leaving the University may have been momentarily painful, but the universal spirit that drives us to be our best selves raised its pesky head again. “I visited with my friend Wayne Andrews at the Powerhouse. I told him I didn’t want to leave Oxford. My kids were happy here, and another shop job would just be doing the same thing.” Wayne Andrews is the Executive Director of the Yoknapatawpha Arts Council (“YAC”) with the wisdom of a sage.

Wayne knew Andi’s talents; if he had had the budget, Andi would have become the education director for YAC. As Andi described it, “We started cooking up a plan.” Wayne offered Andi discounted space at the Powerhouse to run summer camps, and she exposed the community youth to the wonders of the Arts Council.

“Initially, the camps were half-day with a small number of kids. Now, we’re about to start a ten-week season. And I have forty kids a week.”

“Is it the same group all summer?” That was a simple question with a marvelous response.

Andi was effervescent as she described the setup: “Some kids will come every week, every single week. I teach the younger kids, starting at four. I have a staff of eight. One teaches the older children. I get the employees CPR and first aid certified. We start in June, and my lesson plans are right here. I’ve got them all ready.” She pointed to boxes supplied with costumes and colorful accessories for the face, head, and hands.

“Our first week will be Artistic Astronauts—space art. Later, we’ll do magical creatures and art with mermaids, unicorns, yetis, gnomes, and dragons. It’s going to be such fun. She was unstoppable in her description of the program. “The whole summer is like a sampler. We paint, draw, make collages and prints, and some days, we build with clay. So, the kids get to do a little bit of something different each day. Oh, and one week, we’re doing PoP Art with artists like Andy Warhol, Lichtenstein and Jeff Koons.”

How lucky are these children to be exposed to the workings of these artists through the magic and imagination of Andi’s creative bravura—Lichtenstein with his familiar comic strip drawings and Jeff Koons with his balloon dog sculptures? She brings art into their everyday lives. It’s tangible and childlike but, at the same time, as sophisticated as a day at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

“Wayne is very generous with the space at the Powerhouse. We work around church services on the weekends and the occasional wedding.” But that little problem is about to be solved. YAC won a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to create The Humanities Hub project, which will upgrade and expand the usable space at the Powerhouse.

“What about your own art? I know your talent of creating objects of art goes well beyond costume design and summer camp. I love the term “fiber artist, and I understand that’s what the world calls you. Tell me more about it.”

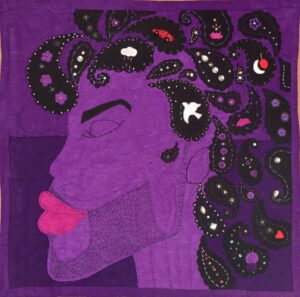

“I won a grant with the Mississippi Arts Commission to do fiber portraits.” In that project, Andi combined her love of music with her fiber arts and wrote a proposal to do portraits of musicians using fabrics and stitchery. “I struggled with the drawing and the nuances of the facial features. And much effort goes into the work before you ever get to the fabric. Bess Currence even commissioned a portrait of her husband John, Oxford restauranteur.”

Her portrait portfolio also includes Willie Nelson, David Bowie, and Stevie Wonder, among many others. Every canvas is consumed by individual stitches, creating the lines and depth of each face. This was the first time I had seen something like it.

“And I teach around the state and in the South. Robert helps me a great deal with that.”

“Robert?” I asked.

Andi smiled. “Robert Saarnio. He loves art and is very supportive. He’s the Director of the University of Mississippi Museum and Historic Houses. We’ve been together for about eleven years.”

“Well, you lucky girl, both of you.”

As she walked me to my car, my thoughts, somehow, drifted to Faulkner. Andi was handed circumstances of unexpected hardship and driving ambition with little room for institutional advancement. She gracefully rose to the immense challenge of raising two girls alone. All the while, she stitched together a remarkable and colorful life of sharing her creative gifts with a town she had never known. Andi is a powerhouse with the heart of a child. She will prevail because she has a soul and a spirit capable of sacrifice and endurance. It is her inexhaustible voice.