Oxford's Music Scene

Where it's been and where it's goingBY LIZZIE MCINTOSH

PHOTOS BY LIZZIE MCINTOSH, PAUL GANDY AND ANDREW PAUL

“It was like the wild, wild west.”

Barry Hannah and Willie Morris sipped on whiskey together after midnight. Bands plucked and sang until the sun came up. There was no judgment, no rules, no fear of law and order to tame them.

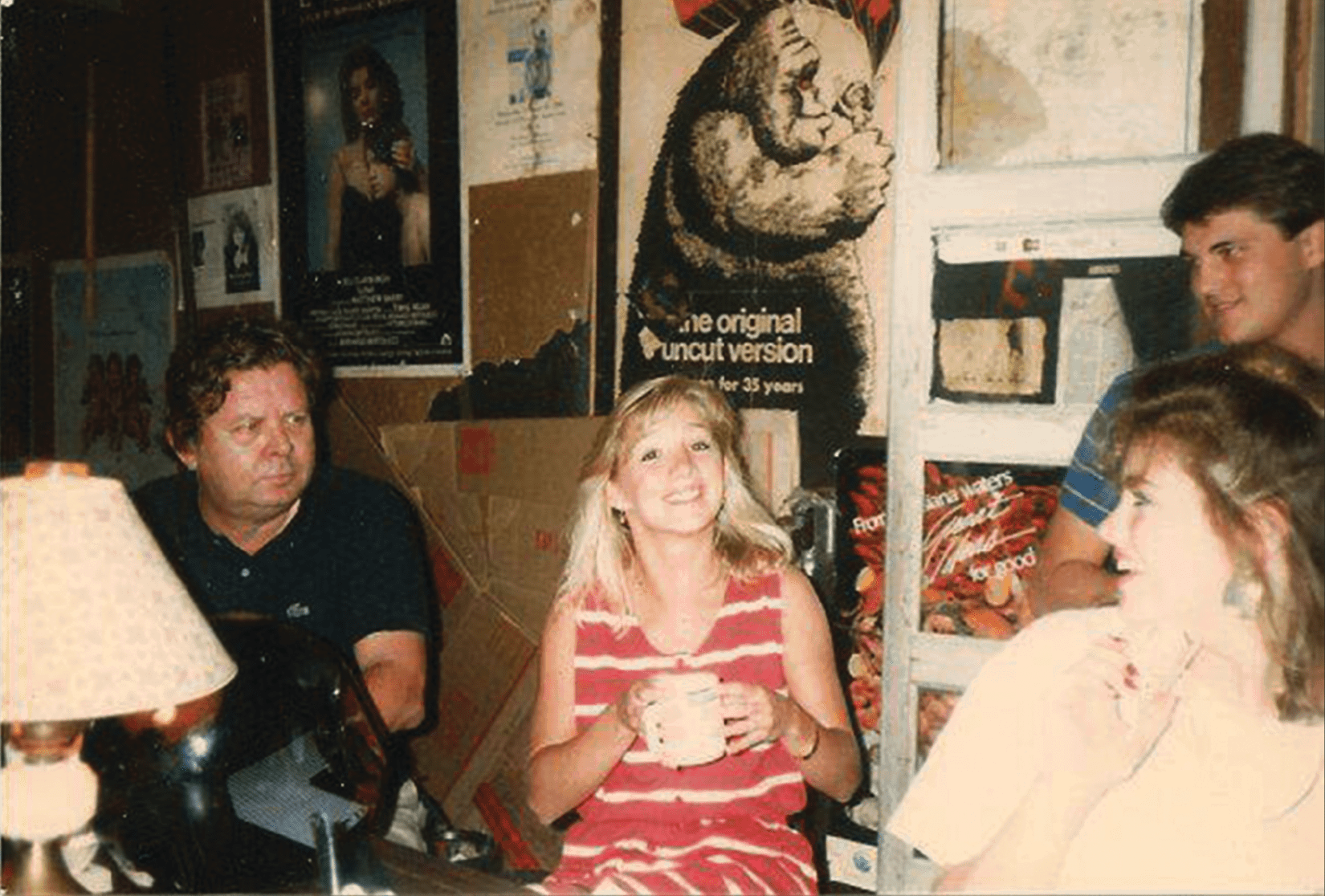

The Tangents and Ronzo Shapiro inside the Hoka. Photo Credit: Fish Michie.

In this Wild West the weapons of choice were instruments, the saloons were the Gin and the Hoka, and the women were groupies of the various bands that played there.

Fish Michie, Mississippi born and raised, was a main player in this Wild West in its heyday — the 1980s, when Oxford’s music scene had an “everything goes” attitude.

“I knew that in 20 or 30 years somebody was going to coming to digging around about that time,” Michie laughs.

Outside of the Hoka Theater in Oxford, Mississippi one night in 1981 sat a sign that read “The Tangents tonight”, written in saxophonist Charlie “Love” Jacobs’ handwriting.

“That’s when the name came about,” Michie explains. “It was because we played everything from Duke Ellington to rock and kind of would go out on a tangent when we played.”

The outside of the Hoka. Photo by Keith Gore Wiseman.

Michie played keys for the Tangents, a band that played that first night together at the Hoka and played there countless nights following. They became an Oxford staple.

Michie remembers one night where band member Jim Dees dressed up like Ray Charles and got someone to carry him to the stage while he covered his version of “Oh What A Beautiful Morning” in sunglasses.

“Dees is like that anyway,” Michie says. “He was just a character and that particular time is indelible in my mind. We were just having fun. I remember it so vividly.”

The Hoka’s walls were decorated in advertisements and announcements of all kinds — from an old Bobby Rush concert ad to one of Charles Evers’ governor campaign posters. They were arranged in no particular order. They just were. They had something to offer for everyone, and that’s just what the Hoka was for its customers. It had a little something for everyone who walked in its doors.

Ronzo Shapiro, now a fixture in Oxford, owned the now-closed Hoka.

“At that time there was like one policeman in town so there was no chance of getting shut down,” Shapiro says. “It was before law and order became so important. It was like Mardi Gras all the time. It seemed like the whole world was available then.”

Willie Morris, far left, spending time at the Hoka. Photo from John Cofield’s Facebook page.

According to Shapiro, there was no need for a liquor license back then. Customers would carry in kegs and other swills of their choice.

“There’s one night that particularly stands out to me,” Shapiro elaborates. “Beanland, the band that George McConnell was in before Panic, was playing one night. The police came in to close us around 4 in the morning. George laughs about me running toward the exit with the money from the night in one hand while giving them the sign to cut off the music with my other.”

That period of time in Oxford seems almost dream-like when conjured in the present. It saw the beginnings of legendary musicians like Jojo Hermann, who also went on to play for Widespread Panic.

“Jojo would play on a beat-up piano at the Hoka. He came from New York and was playing for tips there,” Michie says. “We would play into the wee hours of the morning.”

Early surges in Oxford’s music scene can be credited to the increasing popularity of the Square and the opening of places like the Hoka and the Gin. Until the 1970s, the absence of bars made live performances scarce.

Before the Gin and the Hoka, Oxonians largely found live music on campus, at Fulton Chapel or at fraternity parties, which were the major places to see live music for decades. According to music historian Scott Barretta, university policies discouraged alcohol consumption on campus, which pushed students to the Square.

The first major Square venue was the Gin, located near where Newk’s currently resides on University Avenue. Its next-door neighbor the Hoka arrived around the same time. The two establishments were seen as a package deal.

“We had a really great relationship with each other,” says Shapiro. “Their music would quit at 11:30, and we would start bands shortly after. We weren’t treading on one another.”

The Gin had live music six nights a week and nearly always hosted a full house. Michie remembers playing gigs at the Gin then walking over to play at the Hoka until dawn.

Many people remember the ’90s as a “golden age” in Oxford due to the opening of new venues that nourished the burgeoning music scene. Proud Larry’s started bringing in bigger touring acts; Blind Jim’s, once located above Southside Gallery, hosted notable blues acts, including RL Burnside and Junior Kimbrough.

“Oxford used to be a very sleepy little town — the first bar was in the Holiday Inn (now where the Graduate is located), and then it was basically the Gin,” says Barretta. “Note that others call it ‘the golden age’— not me — and I think that what they mean is that enough venues opened up for there to be a scene.”

Oxford transplant Darren Grem knew about the town’s creative culture before moving around 5 years ago. A professor of Southern culture and a musician himself, Grem wields his own perspective on the climate of Oxford’s music.

“It’s a vibrant town as much as it can be for being relatively small,” Grem notes. “There are fewer stages, but the upside is there is real talent here. There are people here that are just as good, if not better, than people who have signed on the dotted line with record labels.”

And there are people who have had those pens in their hand as well — Bass Drum of Death, North Mississippi Allstars, and Herman and McConnell of Widespread Panic all matriculated the Oxford scene.

Geography also has a positive impact for music lovers in Oxford. Positioned in a sweet spot between Memphis and New Orleans, the town has become a routine tour stop for many larger bands like St. Paul and the Broken Bones, the Alabama Shakes, and the Avett Brothers.

John Barrett and Len Clark from Bass Drum of Death relax outside the Dude Ranch. Photo by Andrew Paul.

But while Oxford can be an incubator for young artists, ultimately local musicians hit a ceiling without a mid-record or major-record label sign. Nashville and New York beckon those who aim for a stable musical career.

That, too, might be changing.

Oxford, with a population of around 23,000, currently hosts five recording studios: Taproot Audio Design, Oxford Recording Studio, Sweet Tea, Fat Possum Records and Tweed Recording. Just up the road, Water Valley is home to Dial Back Sound and Black Wings Studio.

In comparison, Athens, Georgia, whose legendary music scene boasts graduates like R.E.M. and The B-52’s. hosts twelve known recording studios according to Gabe Vodicka, music editor of Flagpole Magazine. With a population of 124,000, that’s just double Oxford’s roster for a town more than five times Oxford’s size.

Still, Oxford’s music culture faces challenges as it looks to accommodate a growing number of students while preserving its character and history. Grem and Barretta both agreed that the scene is still adjusting to what it means to be home to 20,000-something undergrads.

When Barretta moved to Oxford in 1999 as the editor of Living Blues magazine, published by the Center For the Study of Southern Culture at UM, he encountered a music scene very different from today’s, which he attributes to dramatic growth in the student population and a new generation of music-goers.

“The gentrification of Oxford and the massive growth of students who have fake IDs has totally changed the character of the Square,” says Barretta. “Unfortunately there aren’t really too many other places in town where up-and-coming bands can play.”

Barretta adds, “I don’t think that seeing live bands — particularly local bands and mid-level touring acts — is as important to social life as it once was. In the days before social media you often had to go out to bars to be in contact with your friends.”

Barretta also notes that live, guitar-oriented band music has suffered to an extent because of the turn toward electronic music and digital entertainment.

According to Grem, Oxford’s music is rooted in a hill country sound — a stepchild of the blues echoing from the nearby Mississippi Delta. From there the town tilted toward alternative rock in the ‘90s.

“Alt-rock came on to the scene and Fat Possum (a local record label) developed that with a more electrifying, droning sound for the white hipsters that wanted it,” Grem explains.

That sound is still being cultivated in Oxford today.

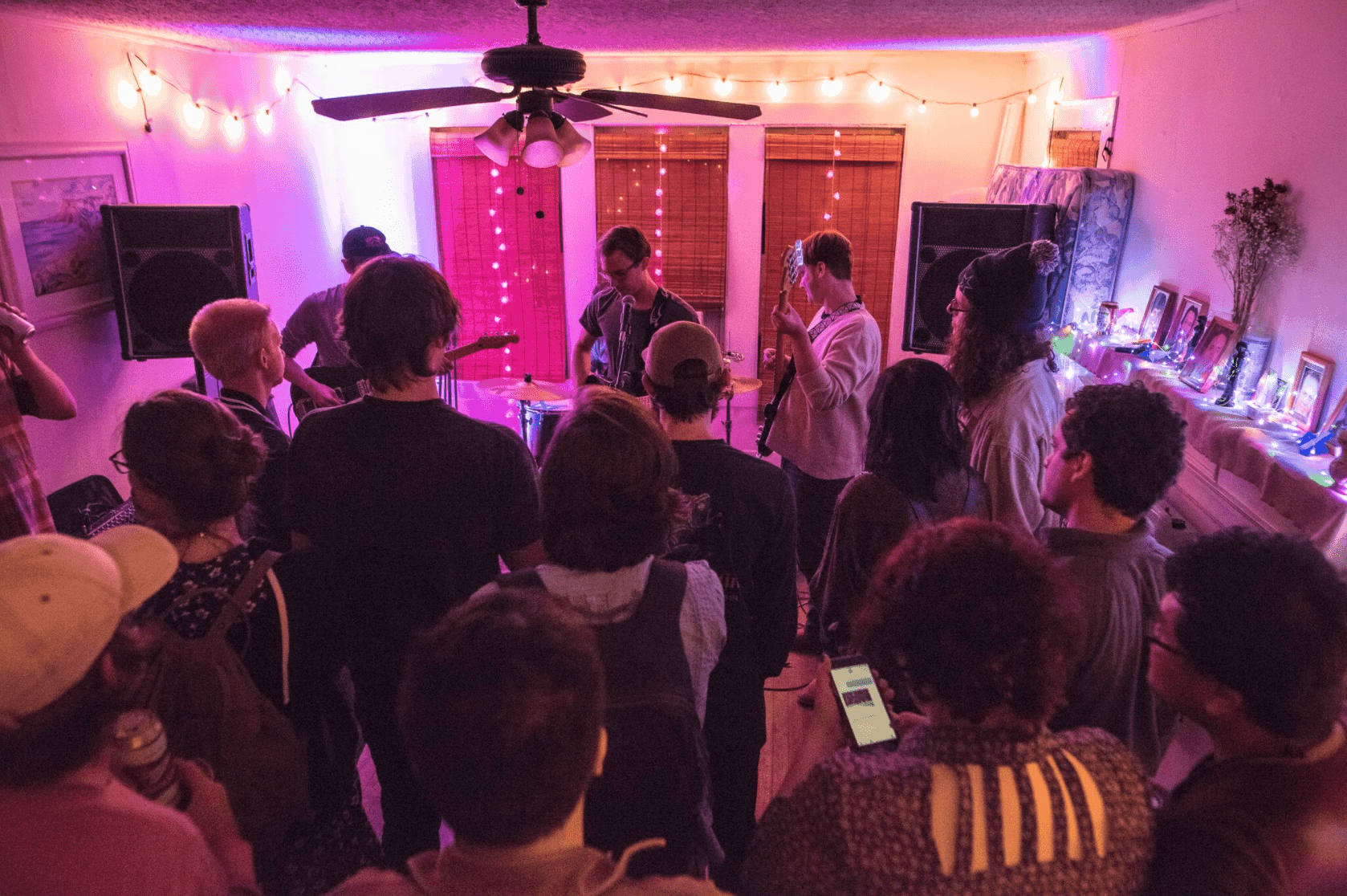

Live music at Rose Room. Photo by Paul Gandy.

Rapid growth and a limited number of venues have created a need for more places for people to play and listen to music locally. Yet there are not as many stages as there were even a year or two ago.

“The structure is a little tricky, but when you have a movement away from your stages that means everybody is trying to get away, and it’s getting outsourced to house parties and places on the outskirts,” Grem says.

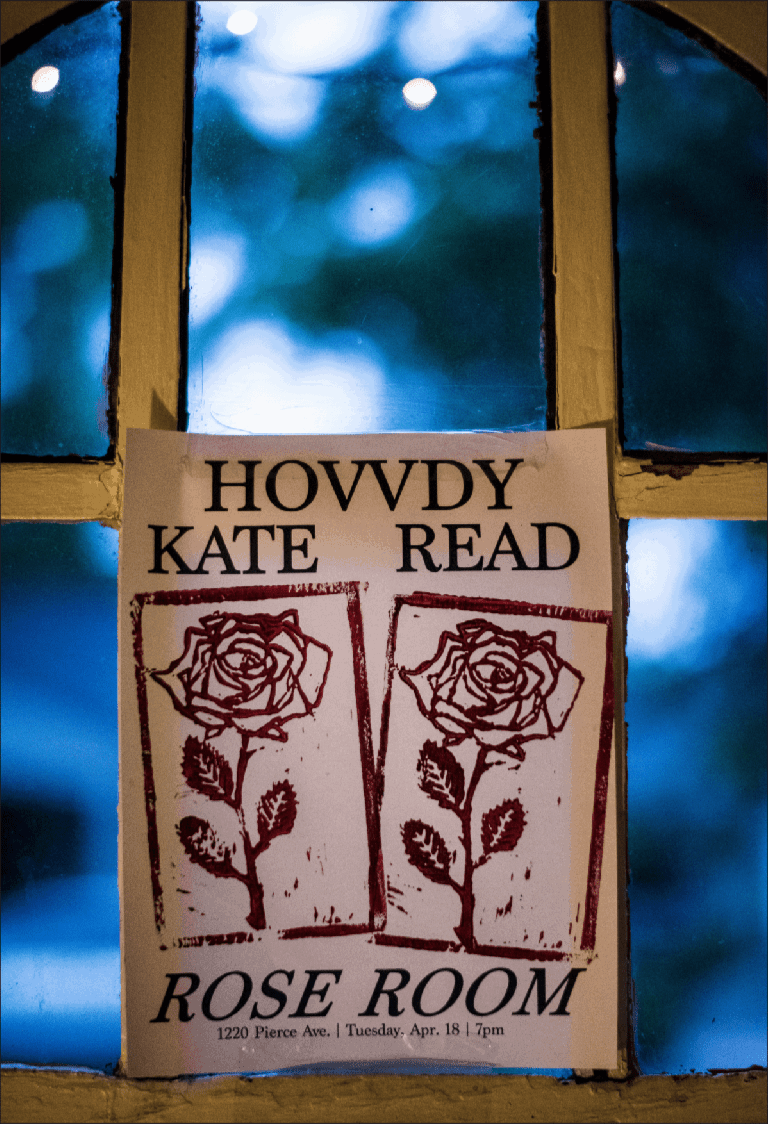

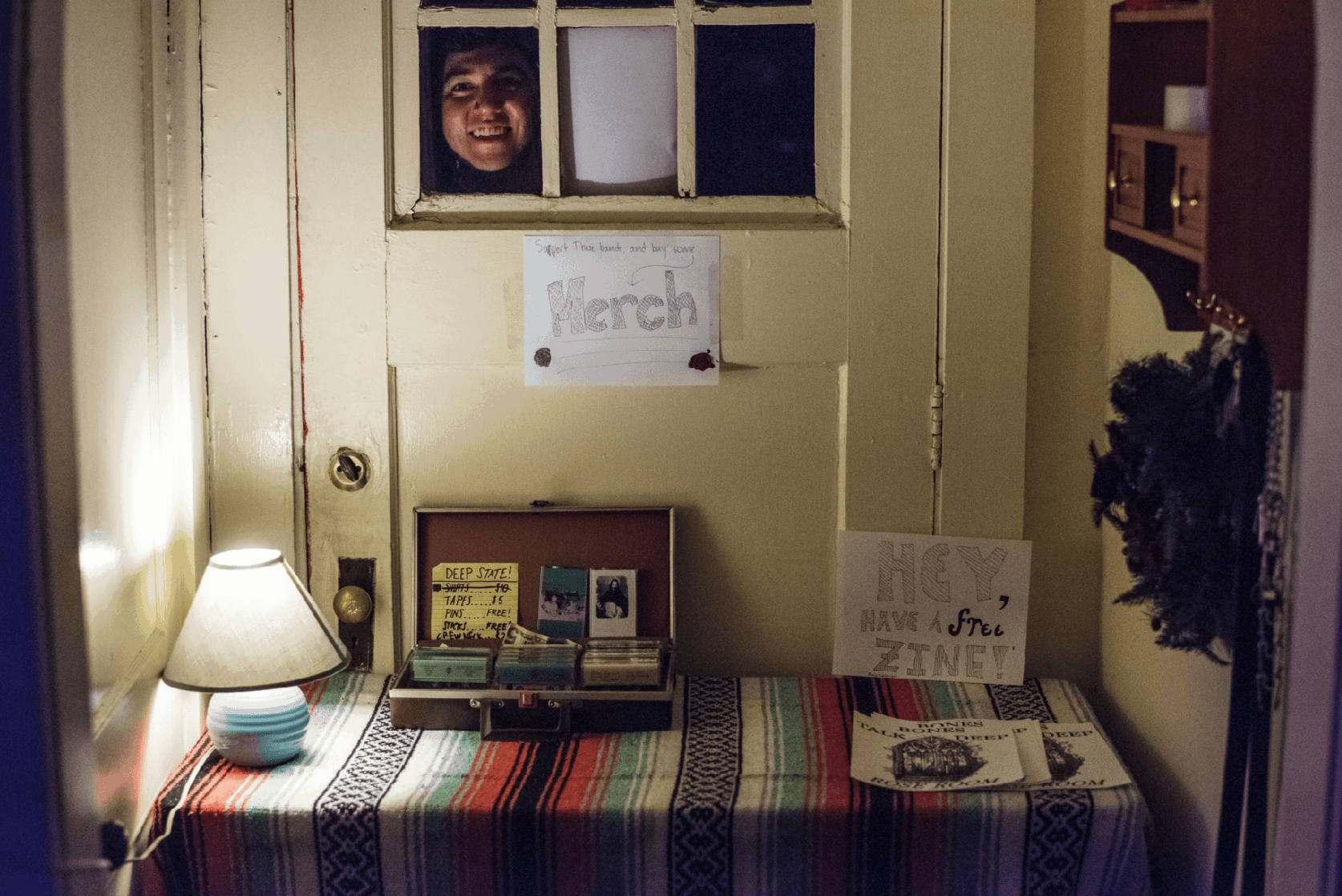

The house party scene has picked up some of the slack for musicians and music-goers. The movement started at the Dude Ranch, then Second Home, both of which closed when occupants moved out of their rentals. The Rose Room, the latest DIY music venue, looks to fill that void by providing another space for local musicians to perform.

Rose Room. Photos by Paul Gandy.

Although shifts in the Square’s culture have somewhat darkened Oxford’s music scene, music is still a part of the small town in a way that is almost unheard of for its size. The movement to underground venues reflects a unique word-of-mouth culture among Oxford’s musicians and promises talented performances for music-lovers willing to seek them out.

“[Students] should know there is more than the local DJ spinning Drake or some kid trying to play blues at Roosters while his friends get hammered,” Grem emphasizes.

“There’s nothing wrong with that, but there’s more to the scene.”